Tracing the Imagined and the Known: Mythical Maps and the Legacy of Real Geography

-Ananya Sinha

Starting with the first civilizations and continuing through the era of satellite photographs, maps have recorded much more than land topography they have mapped the hopes, anxieties, and imaginations of humanity. Even before the development of map-making as a scientific art, individuals mapped the world in terms of myth, legend, and religious belief. These mythical maps were designed as much for spiritual direction and cosmological structure as they were for body location. They positioned sacred cities, divine kingdoms, lost lands, and countries of mythological beings by rivers and mountains. As empirical geography advanced over the years, these imagined places did not become extinct; instead, they transformed, shaping actual explorations, geopolitical stories, and cultural identities.

This essay explores the dynamic relationship between mythical maps and real geography. It investigate how early cartographic traditions balanced imagination with observation, how mythic geographies guided exploration, and in this process shaped modern cultural consciousness. Through examples from Babylonian tablets to fantasy literature, we uncover how mapping has always been a profoundly human act of storytelling founded on both reality and the mythic imagination.

I. Maps as Cultural Texts: More Than Navigation Tools

A map is, by nature, a symbolic construct of space. But in every culture, maps have been also images of belief systems, political agendas, and moral worldviews. Particularly in ancient and medieval cultures, maps have served as cosmological models, organizing the world not just in terms of land and sea but divine order and mythic past.

For instance, the prehistoric Babylonian Imago Mundi (World Image) shows a flat Earth disk with Babylon positioned centrally. Surrounding it is a halo of ocean, and then “regions of darkness,” described in more mythological than geographical terms. This is not documenting land for travel but a worldview that puts the familiar geographic world at the center of cosmic order.

Therefore, maps tend to be visual interpretations of the way societies view themselves—not where they are, but how they exist in the universe and the unknown.

II. Myth Embodied in Ancient Geography

Factual geography and sacred space were often indistinguishable for many ancient societies. Myths were directly embedded in the landscapes and formed geographies that were both real and symbolic.

1. The Greek and Roman Traditions

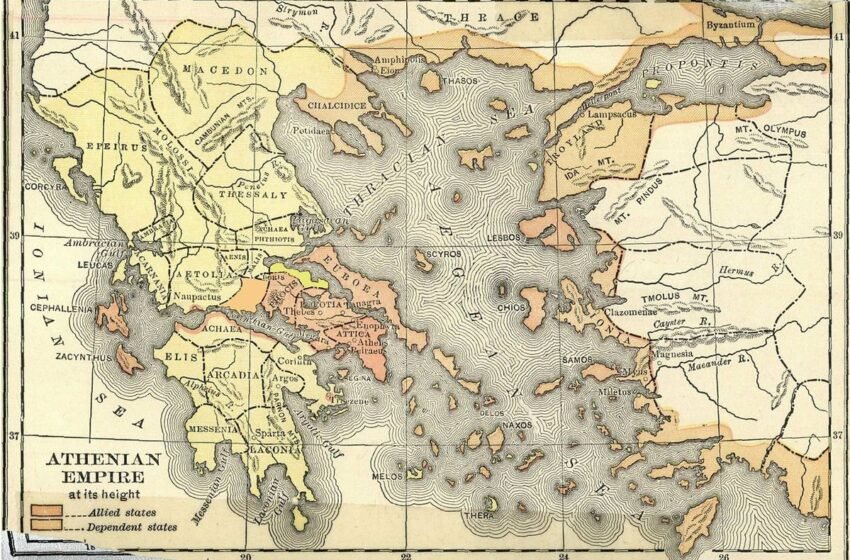

Greek geographers, such as Hecataeus and Ptolemy, attempted to map the world in greater detail. Still, the Greek maps retained space where mythical nations, like the Hyperboreans, lived or had monstrous creatures like Cyclopes and Scythians. These features helped account for the uncharted—turning the unexplored into the imagined.

Romans, continuing this convention, filled their imperial maps with allusions to divine lineage and legend. Thus, the legend of Rome’s founding by Romulus and Remus—reared by a she-wolf—found pictorial expression both in art and in early Roman cartography, reaffirming stories of divine origin and manifest destiny.

2. India’s Sacred Geography

In India, the geography of the subcontinent was—and continues to be—strongly intertwined with myth and religious cosmology. Pilgrimage trails trace routes followed by gods, rivers like the Ganges are sacred personalities, and mountains like Kailash are thought to be houses of gods. Ancient scriptures like the Puranas speak of a round world divided into concentric continents, each divided by seas of varying substances—milk, ghee, wine, and so forth. This cosmology, though not empirically true, embodied religious, ethical, and cosmological truths.

III. Medieval Maps: Myths, Morality, and Theology

In the Middle Ages, maps were not empirical tools but theological diagrams. Perhaps the most well-known example is the Hereford Mappa Mundi (c. 1300), which combines biblical history, classical mythology, and geographic features into a single circular picture of the world.

This map has Jerusalem at its center, a focus for Christian salvation history. At the top to the east is the Garden of Eden, out of reach but existing, and on the periphery are strange beasts and mythical realms: headless men, unicorns, dragons, and the land of Gog and Magog. These were not conceived as whimsical additions but as moral and theological motifs—reinforcing Christian ethics regarding order, sin, and redemption.

Whereas navigational charts known as portolan maps, that appeared in the 13th and 14th centuries, were more practical, even those contained mythic warning signs, like sea creatures or enigmatic islands, symbolizing caution and the ubiquitous presence of the unknown.

IV. Imagined Lands and the Age of Exploration

When global exploration broadened beyond the 15th century, mythic maps adjusted. Actual geography gradually corrected for conjured-up features, but explorers frequently employed myth as a map to the unknown.

1. Lost Continents and Ideal Kingdoms

Maps of the time were crowded with such places as Atlantis, El Dorado, and the Kingdom of Prester John—locales conjectured upon in terms of classical accounts, rumor, or theological yearning. For instance:

Atlantis, in Plato’s description, was conceived as a sophisticated civilization drowned at sea. Although probably allegorical, it was searched for in the world’s oceans and frequently placed on hypothetical maps.

El Dorado, the city of gold, spurred Spanish explorers into the depths of South America, and maps occasionally indicated its hypothetical location.

Prester John, a legendary Christian king in the East or in Africa, made appearances on European maps for centuries, both political aspiration and religious dreaming.

These fictional lands were rationales for exploration and conquest, combining curiosity and ideology.

2. Terra Incognita and Invented Geography

Empty spaces on maps were frequently marked Terra Incognita—”unknown land”—and filled with imaginary creatures, fictional mountains, or fanciful islands. These acted as mental placeholders, providing cartographers room to dream until actual data came their way.

V. Mapping the Sacred and the Symbolic

Numerous maps did not merely illustrate mythical regions—they also mapped religious or philosophical sacred geographies.

1. Pilgrimage and Sacred Routes

Maps of pilgrimage trails, whether to Santiago de Compostela or India’s Char Dham, repeated the sacred geography as much as geography. Pilgrimage routes organized religious experience and gave visual affirmation of one’s path to moral or spiritual completion.

2. Symbolic Orientations

Maps tended to align themselves not northward, as is the case today, but eastward or heavenward, toward spiritual loci. This demonstrates how direction itself was mythologized, with orientation used for moral or cosmological ends rather than practical navigation.

VI. Colonial Cartography and the Politics of Myth

As European empires developed, maps became instruments of political power and cultural fantasy as much as they were of scientific knowledge. Colonizers often imposed Western myths and meanings on the geographies they came to.

In colonial India, for instance, colonial mapping integrated and sometimes reinterpreted sacred geographies, placing rivers such as the Ganges onto administrative maps while frequently bypassing indigenous cosmologies. In other cases, African landscapes were projected onto maps using European projections, mountain chains and rivers surmised on the basis of classical texts or hypothetical imagination, rather than local knowledge.

Maps thus became integral to a narrative of domination—organizing not merely geography, but ideology.

VII. The Legacy of Myth in Modern Mapping

Modern maps are constructed from satellite imagery, GPS technology, and mathematical precision. And yet, the tradition of mythical geography persists—in culture, politics, literature, and the digital realm.

1. National Narratives and Boundary Myths

Contemporary countries tend to keep maps that mirror mythological histories or ideological dreams. Contested borders can be shown as unmistakably belonging to the motherland. Religious landmarks, historical claims, and symbolic borders are strengthened by mapmaking, demonstrating that maps continue to be influenced by narrative as much as numbers.

2. Fantasy Maps in Literature and Media

Modern fiction also carries on the practice of mythical mapping. Writers such as J.R.R. Tolkien (Middle-earth), C.S. Lewis (Narnia), and George R.R. Martin (Westeros) have designed detailed maps in order to situate their fictional worlds. Maps lend spatial realism to created stories and express profound allegorical and moral frameworks.

In cinema, computer games, and virtual reality, map-making has gone digital—yet remains a narrative schema, establishing order for exploration, identity, and change.

Conclusion

Maps are not just directions—maps are reflections of the human soul. Whatever they were inscribed on, in clay, vellum, or pixels, maps have always been something beyond projections of earth. Maps are accounts of how humans envision their position in the universe, how they give meaning to space, and how they dreamt, feared, and believed.

The history of mythic maps shows us that geography is never exclusively physical. It is filled with memory, imagination, and myth. Maps therefore do not merely map the world as it exists on its own but shape the world as we perceive it, believe it, and work to comprehend it.

Even in a scientifically charted world, the legacy of mythical geography persists. It informs art, stimulates exploration, and constructs cultural identities. Amidst a world in flux, the persistence of myth on maps serves as a reminder that human understanding is always inflected with imagination—and that each border, each continent, and each sea has its own tale to share.