Sambhar’s Silent Sovereigns: The Forgotten Salt Traders of Rajasthan

-Vani Mishra

At the center of Rajasthan’s desert sun-scorched landscape rises the Sambhar Salt Lake. India’s largest inland salt lake. A tourist destination today and a center of salt production. But centuries ago, it was the center of a pre-colonial salt economy controlled by a class of influential salt merchants. These merchants, eclipsed by stories of kings and wars, were the inconspicuous architects of an economic empire constructed not of gold or gems but of the salt known to be the “white gold” of the desert. This article explores the profitable past of the Sambhar salt merchants, their peculiar economy of trade, and how the salt of a humble staple long assumed to be taken for granted now defined power, politics, and prosperity in pre-colonial Rajasthan.

Sambhar: Nature’s Bountiful Blessing in a Barren Landscape

The dry geology of Rajasthan and the lack of water never demanded ingenuity to survive. Between the Nagaur, Jaipur, and Ajmer districts is the Sambhar Salt Lake, measuring approximately 190 square kilometres in area and commercially extracting salt since the 1st century CE, even though archaeological findings suggest earlier use. Sambhar Lake is supplied by a range of seasonal streams and as its salinity is very high, it is a perfect place from which to extract salt. Geological conditions of the region, coupled with the fact that it is in the centre of trade routes, made it a point source of salt for centuries. It was not just a natural resource to the local people it was a strategic economic resource.

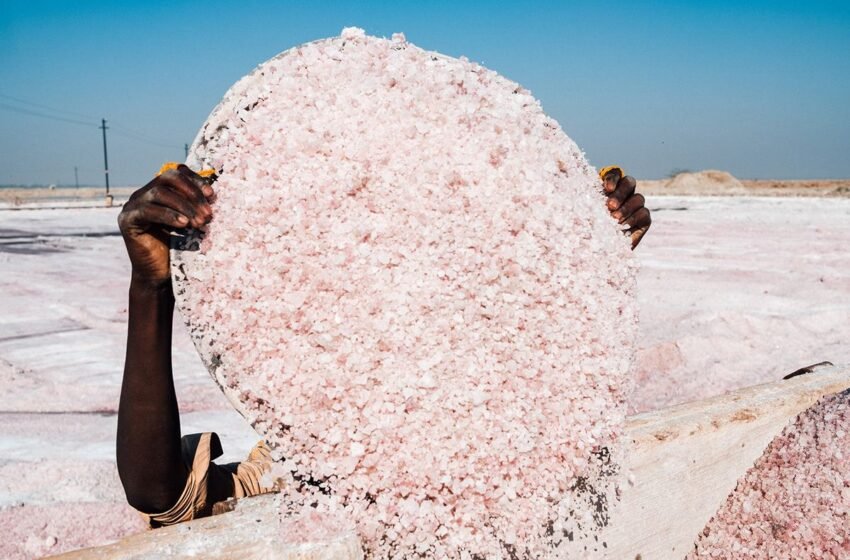

The White Gold

Salt, though ordinary, was once a precious and essential commodity. A prerequisite for food preservation, health, and the performance of trade, salt was the lifeblood of desert societies. And Sambhar, whose vast saline lake shone like a gemstone on the desert landscape, was a natural center of wealth. The Sambhar salt merchants were not just merchants, but tacticians, money men, and haggles. They had an advanced network extended throughout the Indian subcontinent, trading camel caravans, exchange barter, and local markets from Multan to Malwa. In a world where rain was meager and agriculture insecure, salt brought something valuable economic stability. In the pre-modern world, salt was not just a condiment; it was an essential for food preservation, health, and rituals. Its rarity in many inland areas made it priceless, particularly before the introduction of refrigerator technology. Merchants called salt “white gold” because of its high demand and economic value. In Rajasthan, pastoralism and dairying were prevalent, and salt was needed not just for human consumption but for cattle as well. Gujarat, Delhi, Punjab, and even outside the Indo-Gangetic plains dispatched their caravans to Sambhar to sell salt. Sambhar became a node in North India’s pre-colonial mercantile circuit through this long-distance trade.

Salt Merchant Syndicates and the Local Government

The Sambhar salt trade was dominated not by a single state or king but by all, or a group, of the local merchants, caste guilds, and feudal rulers. The Mahajans, typically from the Baniya and Jain castes, dominated the monopoly of conducting the business, work, warehousing, and price functions. They were syndicates that were informal but influential groups who decided who could produce, purchase, or sell the salt in the region.

These merchant guilds were closely allied with the local Rajput princes, Jaipur’s Kachhwahas and the Rathores of Marwar, who provided their protection in return for taxes or tributes. This mutually beneficial and shared power-maintained salt both profitable and stable as a trade commodity. Ironically, Sambhar was also a location where women were utilized within the labor force, primarily in the evaporation pans and the packing. Their work, while often invisible to the eyes of historians, was essential to maintaining the day-to-day functioning of the production of salt.

Salt Roads: Caravans and Trade

Sambhar salt was carried by giant camel and bullock caravans of hundreds of camels and dozens of drivers. The caravans followed fixed salt routes protected by local rulers and regulated by merchants’ private armies. One of the principal trade routes went west to Gujarat, where salt was traded for textiles and spices, and east to the Gangetic plains. The trade was not merely in salt, it promoted cultural exchange, disseminated ideas, and linked far-off economies. Sambhar salt formed part of a greater network of inland trade that ran parallel to the legendary maritime spice routes. To collect taxes and prevent conflict, waypoints and check posts were organized along principal routes. Merchants paid rahadari (toll charges) to local zamindars or rulers who ruled tracts.

The Role of Religion and Ritual

Salt also had strong religious and ritual importance in Rajasthan. Salt was used in purification rituals, funeral rituals, and as an offering to the gods. Both dominant religions in the region, the Jains and the Hindus, valued salt as a mark of loyalty and honesty. Salt was, therefore, not just a commodity — it was of spiritual and moral importance.

A number of merchant clans also commissioned temples, stepwells, and dharamshalas (rest houses) in salt routes as a matter of religion and public benevolence. These remain even today, with inscriptions in gratitude for the role of salt traders in Rajasthan’s architectural and philanthropic heritage.

Sambhar’s Special Legal System

Sambhar was exceptional because of the partially autonomous regime of law that developed around salt. Because there were various kingdoms and mercantile communities in the region, there was a syncretic regime of customary law and trading conventions in place. Price disputes over salt, weights, shipping rights, or labor wages were regularly settled not in royal courts but by merchant panchayats, which are local councils that enforced contracts and settled disputes on the basis of precedent and code of caste. This kind of arbitration-and-regulation system was an extremely advanced economic system that could function in the absence of a central bureaucracy. The Colonial Disruption

The coming of the British put everything on a new track.

Colonial administrators were shrewd and soon realized the profitability of salt.

They levied the Salt Tax and exercised direct control over production and distribution. This heavily drained the power of the merchant syndicates. Legislation was born and Salt Laws were passed. These Laws came to life later with Mahatma Gandhi’s Salt March. This March saw them conduct a trial run in areas such as Sambhar. Local merchants were relegated to the periphery as colonial administrators set aside traditional systems. The close-knit circuits of commerce fell under the weight of centralized control and new taxation regimes. This system compressed a tradition into industry politics. What used to be a proud tradition was now a regulated industry. Whispers of the Past Today

Until now, Sambhar Salt Lake remains functioning and is owned and operated by Hindustan Salts Limited and Rajasthan Salts together.

The erstwhile thriving local salt economy is gone, and all the traditional ways have been lost. The degradation of the environment, over-exploitation of industries, and unpredictable rain have also raised doubts about the lake’s future. However, the tale of the Sambhar salt traders is still narrated in local folklore, abandoned trade hubs, and dilapidated havelis. Theirs is a reminder of the times when business was locally profound, people-oriented, and rooted in the immediate environmental and cultural setting. Conclusion

The Sambhar salt merchants were traders, but they were also guardians of an economic culture that linked deserts and cities, rituals and revenues, and people and power.

Their white gold syndicate was a smoothly oiled machine based on trust, tradition, and territorial diplomacy. In recalling our own tale, we recall also a dream for India’s past in which entrepreneurship and ethics could exist alongside each other, and in which natural resources were not just profits, but prosperity shared. Learning about Sambhar’s salt syndicate is not just history it is about recalling how local economies, if treated with respect and sustainability, can construct strong futures. In an age growing more concerned with global supply chains and monopolistic forms, perhaps there is much to learn from the white gold traders of pre-colonial Rajasthan. Today, Sambhar’s salt pans continue to glint under the desert sun. But the tales of the merchant families, their routes of trade, and their reach are forgotten. With the advent of industrial salt production, their legacy has been relegated to the background. They move on to uncover their legacy and leave it behind in local folk song, tale, and silent pride. Sambhar salt was more than a mineral. They were symbols of power and identity. Their story is a reminder that all empires are not founded by armies. Some are built by people who recognize the value of what lies beneath their feet and who have the courage to take a leap of faith