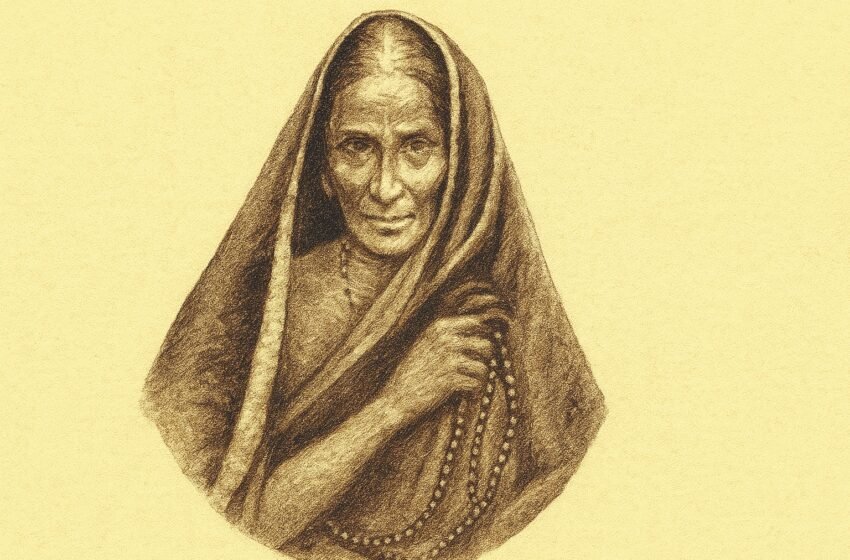

Rashsundari Devi — The First Indian to Write an Autobiography

-Mili Joshi

In the crowded pages of India’s literary history, there lies a name that deserves to shine far brighter than it often does Rashsundari Devi. She wasn’t a queen, a scholar by title, or a revolutionary in the conventional sense. She was, quite simply, a woman who dared to write her life story when the very idea of women reading and writing was frowned upon. In doing so, she gave India its first autobiography.

Let’s pause here. The first Indian autobiography. Not the first by a woman — but the first ever. That fact alone should make us want to know who she was, how she lived, and why her life was such an act of quiet rebellion.

A Life Behind Curtains

Rashsundari Devi was born in 1809 in Potajia village, in what is now West Bengal. Her world was the world of 19th-century Bengal — rich in culture, but tightly bound by tradition. She grew up in a conservative zamindar (landowning) household. Education was meant for men. Women were expected to master the art of silence, the rhythm of the kitchen, and the delicate rules of domesticity.

She was married off at the tender age of 12 to a man named Nilmani Banerjee, a respected member of a landed family. By 25, she was the mother of several children and the manager of a large household. Her daily life revolved around cooking for a joint family, managing chores, and caring for her children.

To us, this may sound suffocating — but for Rashsundari, this was simply life as she knew it. Yet, somewhere in that daily hum of the domestic world, a tiny flame of curiosity kept burning bright.

Learning to Read in Secret

There’s a powerful image that comes up again and again when we talk about Rashsundari Devi: a young woman, hiding behind kitchen doors, holding a scrap of paper, trying to decode the letters in the flickering light of a lamp.

In her autobiography, Aamar Jiban (My Life), she writes about her fascination with the written word. She watched her mother recite prayers from a Chaitanya Bhagavat — a hagiography of the saint Chaitanya Mahaprabhu. Rashsundari longed to read it herself. But there were rules, spoken and unspoken. Women were not supposed to learn letters. In some ways, the act of reading for a woman was considered as improper as shouting in the streets.

But Rashsundari did not shout. She quietly taught herself to read Bengali, first by memorizing letters on scraps of paper she found lying around. Sometimes she would hide pages under her pillow, fearing discovery. She stole moments between chores and prayers. She learned to read in the shadows of her own home.

The Courage to Write

Reading itself was an act of rebellion. Writing? That was almost unimaginable. But Rashsundari Devi’s courage did not stop at learning letters. Around the age of 59, she sat down to put her story into words.

She wrote by hand, on sheets of paper she stitched together herself. She had no formal schooling. She had no model to follow. What she did have was a burning need to tell her story — not just for herself, but for other women like her, who longed to have their voices heard in a world that preferred their silence.

The result was Aamar Jiban (My Life), published in 1876. It is widely recognized as the first autobiography written by an Indian — male or female. The first part came out when she was in her sixties; the second part, an extension, was published in 1906, after her death.

Why Her Story Matters

Aamar Jiban is not just a book; it is a window into the inner world of 19th-century Bengali women — their domestic struggles, their dreams, their fears. It is also an extraordinary record of how knowledge can be an act of resistance.

The prose is simple and direct, like a conversation with an elder who’s seen it all. Rashsundari writes about her joys and sorrows, her longing to read religious texts, her struggles as a wife and mother, her deep faith in God. She shares her regrets and her gratitude in equal measure.

What makes her work so remarkable is that it was not written for fame or praise. She wasn’t seeking to impress anyone. She wrote because she needed to, because writing was her prayer and her defiance rolled into one.

Was Rashsundari Devi a feminist? The word did not exist in her world, and certainly not in her vocabulary. Yet her actions — learning to read, daring to write, giving voice to her experiences — stand as one of the earliest feminist acts in India.

She did not stand on a stage or shout slogans. Instead, she did something far more radical for her time: she claimed her own mind and her own story. In doing so, she left behind a path for generations of women to follow — from writers like Begum Rokeya to modern Indian women who pick up a pen or a keyboard and write their truth.

Legacy and Rediscovery

For a long time, Rashsundari Devi’s work was not widely known outside Bengali literary circles. It was only in the late 20th century that scholars and feminists began to rediscover her contribution and give it the recognition it deserved.

Today, Aamar Jiban is studied in universities across India. Translations are available in English and other Indian languages. Feminist scholars hold up her story as a powerful example of how Indian women claimed literacy as a tool of liberation long before organized women’s movements took root.

She is remembered as the grandmother of Indian women’s writing — a pioneer who wrote when writing was forbidden, and who showed that telling one’s own story is, sometimes, the greatest revolution of all.

What We Can Learn From Her Today

Rashsundari Devi’s life is not a tale locked away in dusty textbooks. Her story speaks directly to us even now. In an age when writing and reading are so easy — when we can publish a thought in seconds — we can forget that there was a time when each letter was fought for.

Her story reminds us that education is precious. That the right to read and write cannot be taken for granted. And that the courage to speak our truth is something we owe not just to ourselves, but to all those who came before us, whispering in hidden corners by lamp light, dreaming of a world where they could be heard.

In Her Own Words

Perhaps the most touching lines come straight from Aamar Jiban itself:

“I had a great desire to read books. I felt as if I would die if I could not read them. I did not know how to read, but I learned it secretly… I have written what I have experienced in my life.”

Simple, clear, and deeply human. That is Rashsundari Devi’s gift to us — a reminder that some revolutions do not roar. They begin quietly, in kitchens and courtyards, carried out by women who refused to accept silence as their only option.

So, the next time you hold a book, type out a post, or share your own story with the world, think of Rashsundari Devi — the first Indian who dared to write her life down. In her story, all our stories find roots.