Clay Chronicles: How Terracotta Sculpted Bengal’s Temple Stories

-Mili Joshi

When we imagine temples in India, we often picture towering stone spires, intricate marble carvings, or grand granite halls echoing with chants. But far from the famous sandstone forts and marble mausoleums lies an earthy, humble medium that has silently preserved centuries of stories — terracotta.

Especially in the floodplains of Bengal and the dry stretches of Gujarat, local clay transformed into sacred art. The temples here might not soar like the gopurams of the South or glitter like the marble shrines of the West, but their walls breathe life, telling tales in burnt clay panels that have survived monsoons, neglect, and time itself.

The Earth Beneath the Shrine

The magic of terracotta begins, quite literally, underfoot. In Bengal’s fertile alluvial plains, clay is not scarce — it’s part of everyday life. It shapes pots, toys, household idols, and, remarkably, temples. When Bengal’s rulers and zamindars — especially during the 16th to 19th centuries — wanted to build places of worship, they looked around for what was abundant. Stones were rare and expensive to transport; clay, however, was everywhere.

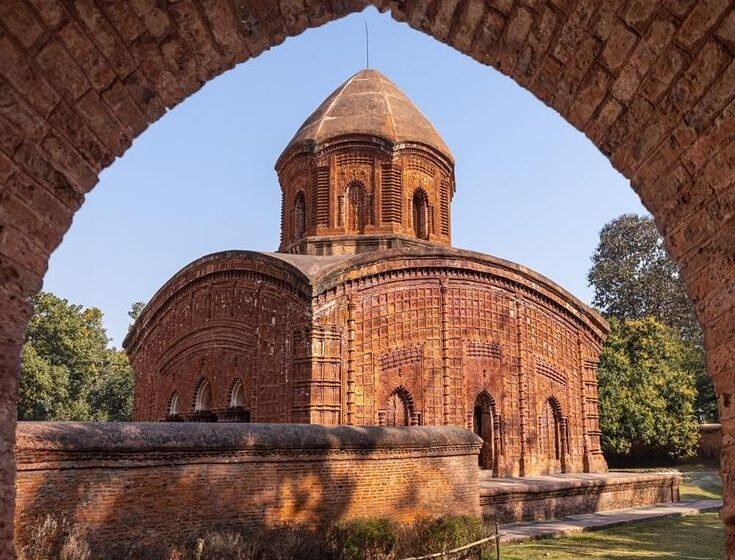

And so, local craftspeople, many from hereditary potter communities, evolved their skills beyond domestic wares to architectural grandeur. Entire temple facades — particularly in the region’s iconic ek-ratna (single spire) and pancha-ratna (five spire) temples — became canvases of terracotta panels.

A Gallery of Stories in Clay

Stand before any old terracotta temple in Bishnupur, Bankura, or Hooghly, and you’ll see a clay chronicle unfold. The panels are not random decorations — they are carefully curated slices of myth and daily life. Gods and goddesses in dramatic poses, battle scenes from the Mahabharata, tales from the Ramayana — all unfurl across rows of baked clay tiles.

The Ramayana panels, for instance, show Rama’s forest exile, the abduction of Sita, Hanuman leaping across the ocean — stories so familiar, yet rendered with a rustic charm unique to Bengal’s artisans. Between divine adventures, the panels surprise you with glimpses of royal processions, hunting scenes, musicians, dancers, and even colonial soldiers on horseback — a quiet testament to the changing world outside temple walls.

Stylistic Signatures

Terracotta art is more than storytelling — it’s also a window into evolving styles. Early temples favored simple, linear carvings. Over time, the panels bloomed into high reliefs with finer detailing — elaborate floral borders, ornamental arches, and figures with expressive faces and fluid movement.

One fascinating feature is how regional motifs sneak in. Lotus medallions, creepers, and riverine animals like fish and crocodiles are common. The attire and jewellery mirror local fashion of the time. Some temples even feature European figures — Portuguese traders or British officers — seamlessly carved alongside deities, showing how artisans adapted their narrative to contemporary realities.

Craftspeople: Unsung Custodians

Behind each panel lies the patient hand of a local craftsperson — often unnamed, often unrecorded. These artisans belonged to communities like the Kumor or Prajapati castes, who passed down techniques through generations. Their work was seasonal and collaborative: clay dug during dry months, shaped and sun-dried, then baked in kilns before being affixed to temple walls with a mixture of lime and mortar.

Unlike stone carving, which required chiseling blocks on site, terracotta allowed artisans to work with manageable clay slabs at home or in small workshops. This decentralized method also meant designs could be highly experimental and locally inspired.

Terracotta Beyond Bengal

Though Bengal’s terracotta temples are iconic, Gujarat too holds whispers of this craft — particularly in its older Shaiva shrines where clay plaques and decorations complemented brick structures. Here, the harsh climate and less frequent rains often meant brick and clay survived where other materials might not.

These regional variations remind us that terracotta wasn’t just a fallback for lack of stone; it was a deliberate aesthetic choice rooted in geography, economy, and local identity.

Echoes of Empire and Archaeology

Terracotta’s story in temple architecture doesn’t stand alone. Archaeologists have found clues to this legacy in earlier sites too — from the Mauryan period’s terracotta figurines to the Gupta era’s decorated brick temples. Each era layered its own motifs and stories onto clay.

In Bengal, the temple boom coincided with the Mughal decline and the rise of local zamindars. Patronage shifted to local deities and village shrines. Clay allowed for quick, cost-effective construction, perfect for smaller feudal lords keen to display piety and prestige without imperial coffers.

As colonial rule advanced, many temples fell into neglect. Yet, these fragile clay panels continued to speak — not just through grand myths but through subtle hints of who we were as a society: syncretic, adaptive, rooted in the land.

A Living Legacy

Today, many terracotta temples stand weathered, their panels chipped by time and rain. Conservationists struggle to protect these delicate surfaces from erosion and human neglect. Yet, the tradition isn’t entirely lost.

In parts of Bishnupur and nearby villages, descendants of temple artisans still shape clay into idols, festival decorations, and souvenirs. Some temples, like the Jor Bangla or Madan Mohan in Bishnupur, attract tourists and scholars alike, rekindling interest in this earthy heritage.

Modern architects and designers, too, find inspiration here. Eco-friendly building materials, vernacular design, and local craftsmanship are making a quiet comeback in an age that’s increasingly mindful of sustainability.

More Than Mud and Fire

Terracotta temples remind us that art and devotion do not always need grandeur in stone or gold. Sometimes, the humblest material — dug from the village pond, shaped by calloused hands, fired in simple kilns — can carry epics across centuries.

Standing before these clay panels, one feels an intimacy rarely found in towering stone shrines. They whisper old tales in an earthy tongue, reminding us that our myths, our makers, and our mud are forever bound — from soil to shrine.

In the end, Bengal’s terracotta temples — and the scattered clay shrines of Gujarat — remind us that history is not just etched in stone but molded by everyday hands and humble earth. These panels stand as quiet witnesses to centuries of faith, artistry, and local life, binding myth to material in a way that feels both grand and deeply human. Preserving them is not just about saving old bricks — it’s about honouring communities who turned soil into stories and reminding ourselves that even the simplest material, when shaped with devotion and skill, can become timeless.