Censorship Laws in India: A Journey from Royal Decrees to the Digital Frontier

-Ananya Sinha

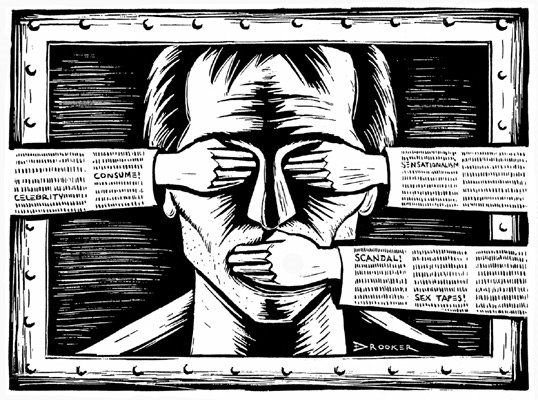

Censorship—government regulation of speech and expression—has existed across human civilizations in one form or another. In India, it has taken many shapes, from religious and royal edicts to colonial control and constitutional democracies. Most recently, the rise of the digital age has introduced new complexities. This article traces the historical arc of censorship laws in India, exploring their roots, transformations, and how they seek to balance state authority with civil liberties.

Ancient and Pre-Modern Controls on Expression

In ancient India, while no formal censorship laws existed, speech and literature were regulated through religious codes and cultural norms. Texts such as the Manusmriti and Dharmashastras emphasized maintaining social order and discouraged criticism of religious or societal hierarchies. Artists, scribes, and poets typically worked under the patronage of kings or temples, making content indirectly subject to approval by their benefactors.

During the medieval Islamic period, blasphemy laws and moral codes based on Sharia law were introduced. Expressions perceived as critical of rulers or religious authorities were often suppressed. Nonetheless, creative traditions such as poetry and music continued to flourish under court patronage, though constrained within accepted religious and moral frameworks.

Colonial Era: The Beginning of Institutionalized Censorship

Under British rule, censorship became a formal legal instrument, especially as print media expanded and nationalist movements gained momentum. The colonial government viewed the free flow of information with suspicion and enacted laws to control dissent.

One of the earliest was the Censorship of Press Act, 1799, introduced by Governor-General Richard Wellesley to curb the spread of French revolutionary ideas. It required publishers to submit content for prior approval—a practice that set a long-lasting precedent.

This was followed by:

- Licensing Regulations (1823): Prohibited printing without a government license.

- Vernacular Press Act (1878): Specifically targeted Indian-language newspapers critical of British rule.

- Indian Press Act (1910): Allowed authorities to demand security deposits and confiscate materials deemed seditious.

These laws were used to silence nationalist voices and revolutionary journalism. Prominent leaders like Bal Gangadhar Tilak and Mahatma Gandhi were frequently prosecuted under sedition and censorship provisions.

Post-Independence Period: Constitutional Rights and Reasonable Restrictions

After independence in 1947, India adopted a democratic Constitution that enshrined the freedom of speech and expression under Article 19(1)(a). However, this freedom was not absolute. Article 19(2) introduced “reasonable restrictions” on the grounds of sovereignty, public order, morality, decency, and more.

Key laws affecting expression post-independence include:

- The Press (Objectionable Matters) Act, 1951: Gave the government powers to curb content likely to incite violence or hatred.

- The Cinematograph Act, 1952: Established the Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC) to review and certify films.

- The Indian Telegraph Act, 1885 (amended post-independence): Permitted interception of communications for public safety.

The Supreme Court played a pivotal role in strengthening free speech during this period. In Romesh Thappar v. State of Madras (1950) and Brij Bhushan v. State of Delhi (1950), the Court struck down pre-censorship practices and reinforced freedom of the press as integral to democracy.

However, this commitment was tested during the Emergency (1975–77) under Prime Minister Indira Gandhi. Press freedom was curtailed, films were banned, and newspapers operated under heavy censorship—highlighting how legal instruments could be used to stifle dissent, even within a democratic framework.

Censorship in Literature, Art, and Cinema

Censorship in India is not confined to political expression; it also affects literature, visual art, and cinema. The CBFC, often referred to as the “Censor Board,” has historically exercised broad authority in determining what films can be shown to the public.

Films like Garam Hawa (1973), Bandit Queen (1994), Udta Punjab (2016), and Lipstick Under My Burkha (2017) have faced cuts or bans due to their political, social, or sexual themes.

In literature, certain works have been banned or restricted for allegedly offending religious or national sentiments. Examples include:

- The Satanic Verses by Salman Rushdie (banned in 1988).

- Nine Hours to Rama by Stanley Wolpert, a fictional retelling of Gandhi’s assassination.

- Soft Target, a controversial book on Khalistani terrorism, authored by Indian journalists.

While India lacks a singular “book banning law,” provisions in the Indian Penal Code (Sections 153A and 295A) are often invoked to prevent publications that might promote communal disharmony or hurt religious sentiments.

The Digital Age: Expanding the Scope of Censorship

The internet has revolutionized communication—and censorship. The Information Technology Act, 2000 introduced legal mechanisms for governing online content. Its Section 66A, which criminalized sending “offensive” messages via electronic means, became highly controversial.

In Shreya Singhal v. Union of India (2015), the Supreme Court struck down Section 66A as unconstitutional, citing its vague language and chilling effect on free speech.

However, Section 69A of the IT Act still empowers the government to block online content in the interest of national security or public order. This provision has been used to block websites, apps, and social media posts—often without transparent processes.

In 2021, the government introduced the Information Technology (Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics Code) Rules, placing increased responsibility on platforms like Twitter, Netflix, and YouTube. These rules require platforms to:

- Appoint grievance officers.

- Remove flagged content within 36 hours.

- Comply with government takedown requests.

Critics argue that while these measures aim to combat misinformation and harmful content, they also pose risks to press freedom and individual expression, especially if misused.

Judiciary: A Guardian of Expressive Freedoms

Indian courts have consistently served as a counterbalance to excessive censorship. Landmark judgments include:

- K.A. Abbas v. Union of India (1971): Upheld film certification but emphasized that censorship must be reasonable and not arbitrary.

- S. Rangarajan v. Jagjivan Ram (1989): Asserted that free speech should only be restricted when there is a clear and present danger.

- Anuradha Bhasin v. Union of India (2020): Ruled that access to the internet is essential for exercising freedom of speech, limiting the government’s ability to enforce indefinite shutdowns.

These rulings reinforce the principle that while restrictions may be necessary, they must always pass constitutional muster and protect democratic values.

Censorship in India has evolved from moral and religious constraints in ancient times to legally codified controls in colonial and post-colonial periods. Today, the line between regulation and suppression remains delicate—particularly in the context of the internet and mass communication.

As India continues to navigate the complexities of a diverse society and a rapidly digitizing public sphere, the real challenge lies in ensuring that censorship, when applied, is proportionate, transparent, and legally sound. A vigilant judiciary, informed civil society, and a free press are essential to upholding this balance between individual freedoms and collective responsibility.