Letters Across Time: The Epistolary Form in Indian History and Literature

In the silent unfolding of history, letters have sometimes cried out more audibly than declarations. Intimate, confessional, persuasive, or poetic, the epistolary form has long been a living thread in the tapestry of Indian life—running from royal courts to revolutionary jails, from partitioned homes to contemporary novels. In Indian literature and history, letters have not merely been instruments of communication but also potent literary objects that store emotion, ideology, and the very beat of a moment. To follow the trajectory of the letter in India is to be faced with love, longing, exile, resistance, and a developing sense of self—grounded in language, relationship, and memory.

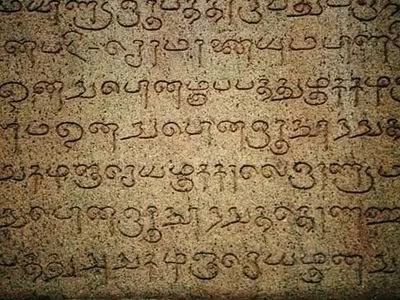

Letters in ancient India were already highly developed in their purpose. The Arthashastra uses the terms espionage and secret communication, showing us the political functions of written letters. In the epics of the Mahabharata and Ramayana, messages are sent both orally and through written letters, carrying emotional as well as strategic significance. The Ramayana is full of situations in which letters—or their oral counterparts—act as go-between between longing and command, exile and homecoming. Hanuman’s mission to deliver Rama’s message to Sita is iconic not only of devotion but of the strength of direct communication in the face of epic strife. These early scenes presage the complex role letters would eventually assume in subsequent Indian literature and politics.

During the medieval era, the science of letter-writing prospered in royal courts and among Sufi tradition. The Insha literature—collections of sample letters in Persian—were both functional and beautiful. The letters, frequently designed with ornate metaphors and poetic embellishments, embodied courtly refinement and bureaucratic complexity. They provide contemporary historians with a window on the cultural and administrative textures of the time as well. Letters were not just pieces of paper; they were formalized enactments of wit, fidelity, yearning, and sometimes even subversion.

The Bhakti and Sufi traditions introduced a personal and affective note into letter-writing. Poets such as Mirabai and Kabir wrote in styles that frequently assumed the form of letters—to the absent other, the lover, or God itself. These were devotional, rebellious, and deeply personal epistles. In the poetry of Mirabai, the figure of Krishna as the far-off beloved repeatedly imitates the literary tradition of a letter penned in exile or longing. In this context, the letter becomes at once metaphor and form—a means for stating the unstateable, an outcry transmitted into the void.

By the colonial era, the letter was assigned a different level of seriousness and purpose. As the British Empire expanded its bureaucratic reach, letters became tools of administration, education, and resistance. Indian reformers, revolutionaries, and writers turned to the epistolary form to negotiate identity, authority, and rebellion. The personal letter became political. Mahatma Gandhi’s letters, for instance, straddle the line between public discourse and private reflection. His letter to Lord Irwin, pre-Salt March, is the classic instance of epistolary as political strategy—adamant, courteous, and morally compelling. It’s a letter with the gravity of history behind it, both rhetorically precise and personally felt.

Other freedom fighters, similarly, left behind epistolary legacies that map the inner territories of battle. Jail letters, such as those of Jawaharlal Nehru to his daughter Indira, are notable for their combination of education, emotion, and political teaching. In Glimpses of World History, Nehru converts his prison isolation into an epistolary classroom. In these letters, he not only communicates with his daughter but also builds a secular, humanist world vision. The letter becomes a pedagogical space, informed by love and idealism. In the same way, Bhagat Singh’s prison letters are not only testimonies of his ideological conviction but profound emotional insights into the morality of sacrifice and resistance. They are letters as testament—written knowing that they will survive him.

In fiction, the epistolary novel introduced itself to Indian writing in English with elegance and innovation. The genre provided means to combine narrative closeness and social commentary. Ruth Prawer Jhabvala’s Heat and Dust, half-written in letters and diary writings, compares the two women’s experiences of India across generations. The broken-up, subjective style of the novel enables the reader to live history not as chronological sequence but as palimpsest—layered, unstable, and intensely intimate.

Arundhati Roy’s The God of Small Things does not adhere strictly to the epistolary mode, but it does contain strong epistolary moments of writing that capture the characters’ loneliness and longing. Velutha’s unmailed love letters, Ammu’s fragments of confession, and Estha’s silences are all components of an emotional epistolary weave that captures longing, loss, and repression. In those moments, the letter is the final refuge of a suppressed voice—a cry locked inside paper, usually never heard by its intended reader.

In regional Indian literature, the letter form has had a profound presence as well. In Urdu literature, the khat (letter) tradition flourished, particularly in the 19th and early 20th centuries. The letters of Ghalib, especially, are masterpieces in their own right. With his wit, melancholy, and philosophical bent, Ghalib turned everyday communication into high art. His letters blend poetry and prose, self-irony and existential musing. In a letter, he acknowledges that he writes not to inform but to be less alone—a feeling that bridges time.

Among Bengali writing, Rabindranath Tagore’s letters constitute a form in themselves. His Chinnapatra (Torn Letters), written to his niece Indira Devi, are lyrical, reflective, and philosophical. The letters, although originating in personal sentiment, span aesthetics, nature, and the divine. Tagore’s writing in these epistles tends to sound almost like verse, and they provide a glimpse into his changing philosophy. His letters to Mahatma Gandhi and other contemporaries, on the other hand, are political and engaged–addressing his issues with nationalism, education, and modernity.

The Tamil author Subramania Bharati employed the letter format in journalism and poetry in order to address the reader directly, with both the colonial state and fellow citizens, with urgency and lyricism. His fantasy epistles to Mother India are angry, sensitive, and transformative. In Dalit writing as well, letters have been used to subvert caste hierarchies and ask for dignity. Bama’s Karukku, while more autobiographical in nature, is interspersed with the direct address tone—nearly akin to a letter to the reader, asking the reader to observe, feel, and transform.

In newer Indian fiction, too, the epistolary structure has been rediscovered with freshness. Aravind Adiga’s The White Tiger is set as a series of long letters from the main character Balram to the Chinese Premier, visiting India. This letter is more than a literary device; it is a transgressive act—a murderer’s confession, an entrepreneurial confession, a social climber’s confession. Balram’s voice is apologetic neither, cunning as a fox, and brutally candid. By the letter form, Adiga satirizes class, corruption, and the illusion of progress in contemporary India.

In another vein, the novel I Have Become the Tide by Githa Hariharan interweaves letters and testimonies to tell the histories of Dalit struggle and student resistance. The epistolary fragments provide several voices, interrupting linear narrative and producing a chorus of dissonant voices. This polyphonic employment of letters allows the novel to resist closure—keeping the dialogue open, living, and unfinished.

The letter form, by Its very nature, is a space of vulnerability. It captures people mid-thought, often unsure, hopeful, or afraid. This vulnerability is what makes letters so powerful in literature. They are places where characters and real people drop their masks. In contrast to public speech, which is performative, the letter is private—written for one, read by many. And in that tension lies its magic.

Besides, letters are peculiarly poignant as part of the genre of Partition writing. Love letters between partitioned families, love letters of separated lovers torn by newly redefined borders, and torn families broken by religious lines are devastating documents of dislocated personal history. Saadat Hasan Manto’s piece Khol Do doesn’t consist of a letter, but the unthinkable breakage that a letter may have been trying to rectify is alive within it. By contrast, most of the oral histories of 1947 contain tales of letters written and never returned—of names changed, of silence being the sole response. The letter, in these instances, is a ghost—a remnant of what was once home.

In Indian film too, the letter has been at the center of story and feeling. Garm Hava, Pakeezah, or Sita Aur Geeta employ letters to disclose secrets, advance plots, or spark dramatic turns. The visual trope of the unopened letter, the ripped note, or the last message before dying—these are filmic tropes whose emotional force derives from the profound cultural space letters occupy in Indian memory.

Now, in the era of instant messaging, emails, and disappearing texts, the letter written by hand may appear old-fashioned. And yet, there is a renaissance of sorts—a sentimental return to the epistolary novel. Initiatives such as “Letters to the Beloved,” “Postcards from Prison,” or “Letters to a Young Poet” workshops in India are reclaiming the slowness, thoughtfulness, and closeness of letter-writing. Even in modern digital fiction, the form of the letter—its directness, its second-person address—is being employed to construct immersive and emotionally engaging narrative.

The epistolary genre has also crossed over into protest. Letters to the state, petitions in the voice of the citizen, open letters by artists and intellectuals—all these genres carry on the tradition of the letter as a means of resistance. When 49 well-known Indians wrote to the Prime Minister in 2019 against growing hate crimes, and were subsequently booked on charges of sedition, it became evident that even now, a letter can shake power.

Essentially, the letter in Indian literature and history is not a fixed form—it is a living, changing reflection of society. It has been used by kings and revolutionaries, poets and lovers, reformers and children. It has borne the burden of exile and the gentleness of reunion. Its strength is in its intimacy—and in the fact that it is not afraid to speak directly, one voice to another, across time.

As we scroll through our lives at increasing velocity, maybe we can stop and recall the letter—not as an artifact, but as a reminder. A reminder that words have more weight when they are considered, that expression is a conversation, and that literature, in its most human, frequently starts: Dear You…