The Ghazal as a Mirror: Love, Loss, and Longing Across Time

The ghazal, with its rich imagery and intensely emotional undertones, has crossed centuries and geographies, retaining its core while imbibing the hues of every culture it came in contact with. The ghazal, an originally Arabic poetic form, was born in the 7th century, focusing mainly on love, loss, and the agony of separation. Over time, it journeyed through Persia, where it flourished in the works of poets like Rumi and Hafiz, eventually making its way into the Indian subcontinent. In every region, the ghazal adapted itself to local languages and sensibilities, yet its core—the portrayal of longing and spiritual or romantic yearning—remained unchanged.

A typical ghazal Is composed of a series of couplets (sher), each standing independently in meaning, yet linked thematically. The initial couplet presents a rhyme and refrain, which all others subsequently replicate. This repetitive form imbues the ghazal with music and rhythm, further intensifying its emotional power. The poet or ‘shayar’ frequently initials the last couplet with the pen name (takhallus), introducing a personal note which merges the poetic self with actual self. By this means, the ghazal is not only a literary exercise but an intensely personal, even confessional, act.

The reason the ghazal stands out is that it is both specific and universal. On the one hand, it typically tells the intensely personal story of the poet; on the other, it describes universal themes that anyone who has ever loved and lost can identify with. The beloved in a ghazal is frequently unattainable, elusive, or even cruel, yet the figure of the beloved is not always a person. The beloved may be an ideal, a dream, or even a higher power. This ambiguity creates a level of depth in which the ghazal can function at two levels: both romance and spirituality.

In Persian literature, the ghazal came to be used for mystic expression. Sufi poets employed the vocabulary of love to explain the soul’s yearning for God. The anguish of separation from the beloved replicated the spiritual seeker’s alienation from the divine. Hafiz, for example, wrote ghazals that may be interpreted both as romantic longing and as metaphor for spiritual rapture. This layering of significance became a characteristic of the ghazal, providing readers with several interpretations based on their spiritual or emotional condition.

When the ghazal reached the Indian subcontinent, it found fertile soil in Urdu. The fusion of Persian aesthetics with Indian cultural sensibilities resulted in a rich tradition of Urdu ghazals that resonated with the hearts of many. Poets such as Mir Taqi Mir, Ghalib, and Faiz Ahmed Faiz reconfigured the form, giving it depth of philosophy, personal suffering, and political resistance. Mir’s ghazals tended to be melancholic in introspection, Ghalib’s by existential questioning and irony, and Faiz led the form into the arena of revolution, speaking in the idiom of love about social injustice. In each instance, love was at the heart, but it was love pulled to its furthest metaphorical limit.

Another of the ghazal’s long-lasting strengths is its capacity to speak the unspeakable. It finds words for a sort of holy pain, whether that pain is that of a lost beloved, the silence of God, or the wounds of a broken world. The ghazal offers no promise of resolution. Whereas Western styles tend to demand closure or advancement of the narrative, the ghazal pauses in a field of suspended yearning. It orbits the pain, buffs it like a gemstone, and displays it openly for everyone. This may well be why the ghazal has endured as long as it has—it reflects the emotional truth that not everything heals, and not everything resolves.

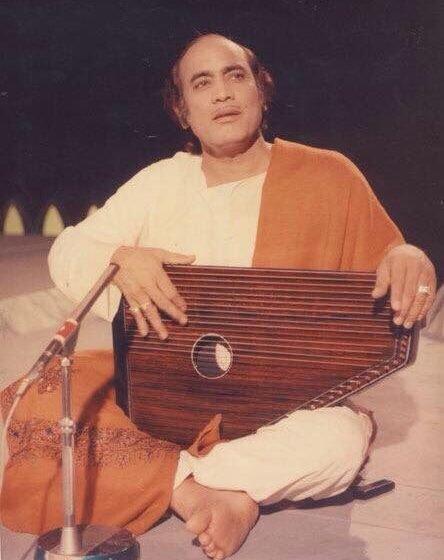

The ghazal also translates very easily to music, which has preserved and made it popular over the centuries. Ghazals became part of Indian and Pakistani classical and semi-classical music traditions. Begum Akhtar, Mehdi Hassan, Jagjit Singh, and Ghulam Ali made ghazals popular with the masses by mixing complex poetry with melancholic melodies. The musical ghazal is not a performance but an emotional outpour. When performed, the ghazal breaks down language and culture barriers, communicating with the soul itself.

Even today, the ghazal continues to develop. Modern poets are experimenting with its structure and themes, composing ghazals in English and other Indian languages. Agha Shahid Ali, one of the best-known contemporary ghazal writers in English, popularized the form internationally with his book Call Me Ishmael Tonight. His ghazals preserved the traditional form but broadened its vocabulary to accommodate contemporary imagery, from airports to exiles, blending the old and the new with ease. His work shows that the ghazal is not a dated relic but a living, breathing form that can speak to contemporary anxieties and diasporic identity.

The ghazal has also gained new voices in Hindi literature. Hence, Dushyant Kumar, for instance, used this very form to criticise the conditions of politics and social lethargy. Others use it to express personal sorrow and existential speculations. Politics does tend to straitjacket the divide between Hindi and Urdu; however, it remains unhindered by words in the realm of ghazals. Linguistic hybridity alone makes a ghazal long-lasting – the capacity to belong to many tongues at one time and to none at all.

On a personal note, reading or writing a ghazal can be a healing experience. It permits one to stay with sorrow, to give it a name, and to discover its beauty. The ghazal is a teacher of patience—it does not hurry to solutions or shallow consolation. Rather, it welcomes the reader into a contemplative place, where loss is not to be erased but to be respected. In a world that too often requires closure and certainty, the ghazal’s acceptance of ambiguity is a subtle act of defiance.

Additionally, the ghazal reflects the human experience in its disjointed state. Each couplet is independent, similar to moments in life that can feel disconnected but create a unified emotional path when considered as a whole. This mosaic-like composition enables the poet to address the same theme from various perspectives, providing a panoramic view of the landscape of the heart. Love, in the ghazal, is not one emotion but a multifaceted mixture of hope, despair, joy, and agony. It is as much about yearning for presence as it is about mourning the absence.

In the hurly-burly of modern life, the ghazal’s measured, slow pace can feel like a healing balm. It makes us linger, to feel, and to put that feeling into words that are both elaborate and exact. Even for readers not familiar with its specialised lexicon, the emotional appeal of the ghazal is instant. Whether it’s the eerie echo of a sher or the quiet turn of irony in the last couplet, there is always something in a ghazal that stays with you—like scent on an old letter, or the echo of a voice heard years ago.

In an era of speed, the ghazal’s measured, unhurried pace can feel like an anodyne. It invites us to slow down, to sense, and to express that sensing in words that are both elaborate and exacting. Even for readers not familiar with its classical diction, the emotional pull of the ghazal is instant. Whether it is the eerie echo of a sher or the faint turn of irony in the last couplet, there is always something in a ghazal that stays on—like fragrance on an old letter, or the echo of a voice heard years ago.

The journey of the ghazal, from the Arabian deserts to the Mughal emperor courts, and then to the radio frequencies of the 20th century, is a tale of cultural adaptation and survival. In the Delhi Sultanate and Mughal era, Persian was adopted as the court language, and the ghazal found its way into Indian literary tradition through poets such as Amir Khusrau. The fusion of Persian refinement and Indian imagery bred Urdu, the language perfectly suited to the emotional nuance of the ghazal. Through time, the ghazal became an image of Indo-Islamic taste—its metaphors borrowed from gardens, wine, nightingales, and aching heart.

The colonial period saw another transformation. In British rule, ghazals were used as coded resistance, mourning lost glory and resonating the emotional intensity of dispossession. Poets such as Bahadur Shah Zafar, the final Mughal emperor, composed ghazals in exile that grieved not just individual loss but the disintegration of an entire civilization. Here, the ghazal was a cultural archive—a soft record of a world in decay.

In the 20th century, as India and Pakistan emerged as separate nations, the ghazal crossed borders not just politically but musically. Ghulam Ali, born in 1940 in Kaleke, Punjab (now in Pakistan), emerged as one of the most influential ghazal singers post-Partition. Trained in both classical music and the tradition of thumri, Ghulam Ali brought a fresh dimension to ghazal singing—where vocal mastery met lyrical subtlety. His capacity to find his way through the emotional rhythm of a sher, to transform pauses into pathos and inflections into intimacy, made him a bridge between classical tradition and modern sensibility.

It’s difficult to imagine that anyone personifies this timeless emotional appeal so eloquently than Ghulam Ali, whose voice transcended verses and rendered them as velvet. His take on the old Akbar Allahabadi penned 19th-century masterpiece of a ghazal in the form of “Hungama Hai Kyon Barpa” is an illustration in point on the ghazal’s potency in mixing irony, poise, and pining into something evocative:

Hungama hai kyon barpa, thodi si jo pee li hai

Daaka to nahi daala, chori to nahi ki hai

(“(Why all this fuss, when I’ve only had a small amount to drink?

It’s not as if I burgled anyone or stole anything.”)

The original poet, Akbar Allahabadi, lived during British colonial rule, and his poetry often critiqued the social hypocrisies and political absurdities of the time. Ghulam Ali’s rendition, though steeped in melody, carries this historical nuance, echoing the unease of a colonized society veiled in satire. The ghazal here becomes both timeless and time-bound—a reflection of a specific historical consciousness and a universal human condition.

In short, the ghazal is not just a form of poetry—it is a mirror that reflects our most profound feelings, particularly those we tend to have trouble articulating. But it is also a witness to history. It has soaked up centuries of cultural, political, and personal turmoil, coming out each time with new depths of meaning. From the whispered supplications of the Sufi mystic to the revolutionist’s cryptic protest, from the imperial court to the post-Partition boards, the ghazal keeps singing of love, loss, and desire. And by doing so, it promises us that though hurt is unavoidable, it can be made beautiful as well—and that longing, as much as it might never let up, is a form of presence itself.

Finally, the ghazal is not just a poetic form—it is a mirror that shows us our deepest feelings, particularly those we usually find it hard to say. It is a tribute to the timelessness of language to contain the nuances of human life. Through centuries and geography, from Persian courts to Indian concert halls, from recited couplets to computer screens, the ghazal continues to sing of love, loss, and yearning. By so doing, it guarantees us that though pain is unavoidable, it can be lovely too—and that yearning, even though it might never cease, is a form of presence itself.