The Opium Wars (1839–1860)

The Opium Wars, fought between China and Britain in the mid-19th century, were among the most consequential conflicts in modern Chinese history. These wars, driven by Britain’s aggressive trade policies and China’s resistance to the opium trade, resulted in a significant weakening of the Qing dynasty. The wars exposed China’s vulnerabilities, led to the loss of sovereignty, and marked the beginning of Western imperial domination in China. This article explores how Britain’s trade in opium destabilised China, the events that led to war, and the long-lasting consequences that shaped China’s political and social landscape for the next century.

The Roots of Conflict: Britain’s Opium Trade in China

The Trade Imbalance

Before the Opium Wars, China had a self-sufficient economy with little need for foreign goods. The Qing dynasty (1644–1912) controlled trade with Western nations through the Canton System, which restricted foreign merchants to a single port—Guangzhou (Canton). While Britain had a high demand for Chinese goods such as tea, silk, and porcelain, China required little from Britain in return. This trade imbalance led to a substantial outflow of silver from Britain to China, causing economic concerns for the British government.

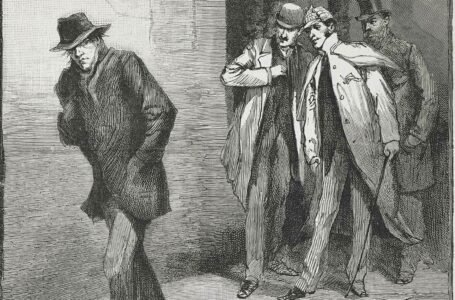

To reverse this imbalance, Britain began exporting opium to China. Opium, a highly addictive narcotic derived from the poppy plant, was grown in British-controlled India and smuggled into China through Chinese merchants. By the early 19th century, opium addiction had become a widespread problem in Chinese society, affecting millions, from peasants to government officials. The British East India Company and private traders profited immensely from this illegal trade, while China suffered social and economic devastation.

The Devastating Effects of Opium in China

The opium trade had catastrophic effects on Chinese society. Millions of people became addicted, leading to a decline in productivity and severe health crises. The Qing government recognised the dangers and attempted to suppress the trade. Additionally, the outflow of silver used to pay for opium caused inflation, weakened China’s economy, and reduced the government’s ability to fund essential services. Corruption among officials further exacerbated the crisis, as some were bribed to allow the opium trade to continue.

By the late 1830s, the Qing government faced growing pressure to act. Officials, scholars, and reformers called for stricter measures to eliminate opium consumption and punish those involved in its trade. This mounting tension would soon erupt into open conflict between China and Britain.

The First Opium War (1839–1842)

Commissioner Lin Zexu’s Crackdown

In 1839, Emperor Daoguang appointed Lin Zexu, a staunch anti-opium advocate, as Imperial Commissioner to eradicate opium from China. Lin took decisive action, confiscating and destroying more than 20,000 chests of opium (approximately 1,200 tons) in the port of Humen, near Canton. He also expelled British merchants involved in the trade and wrote a letter to Queen Victoria appealing to Britain’s moral conscience, though it went unanswered.

The destruction of opium enraged British traders and the British government, which viewed it as an attack on private property and free trade. In response, Britain dispatched its navy to China, launching the First Opium War.

British Military Superiority

China was unprepared for war against Britain’s advanced military forces. The British Royal Navy, equipped with modern steam-powered warships, easily outmanoeuvred and defeated the outdated Chinese fleet. British troops, armed with superior rifles and cannons, overwhelmed Chinese forces in a series of swift and decisive battles. Key cities such as Guangzhou and Shanghai fell quickly, highlighting the Qing dynasty’s military inferiority and lack of technological advancements. After several defeats, China was forced to surrender, and in 1842, the war officially ended with the signing of the Treaty of Nanjing, the first of many “unequal treaties” imposed by Western powers. Under the terms of this treaty, China was required to cede Hong Kong to Britain, open five major ports—Guangzhou, Shanghai, Xiamen, Ningbo, and Fuzhou—to British trade, pay a large indemnity, and grant extraterritorial rights to British citizens, allowing them to be governed by British rather than Chinese laws. This treaty deeply humiliated China, further weakening Qing authority and setting a precedent for increased foreign intervention. Despite these concessions, the opium trade remained unchecked, fueling tensions that would ultimately lead to renewed conflict in the coming years.

The Second Opium War (1856–1860)

Renewed Conflict and Western Aggression

By the 1850s, Britain and France sought to expand their privileges in China. Using the pretext of minor diplomatic disputes, they launched the Second Opium War, also known as the Arrow War. The Qing government, already weakened by internal rebellions such as the Taiping Rebellion (1850–1864), struggled to resist.

British and French forces, using advanced weaponry and superior naval power, attacked Chinese coastal cities and marched towards Beijing. In 1860, they looted and burned the Summer Palace, a symbol of Qing imperial power, in an act of revenge and intimidation. The war ended with the Treaty of Tianjin (1858) and the Convention of Beijing (1860), which marked another devastating blow to China’s sovereignty, forcing the Qing government to concede to harsh foreign demands. These agreements granted Britain, France, Russia, and the United States the right to establish permanent embassies in Beijing, undermining Qing authority over diplomatic affairs. Eleven additional treaty ports were opened, increasing foreign access to both coastal and inland trade hubs. Most significantly, opium was fully legalised, worsening China’s economic dependency and deepening the social crisis caused by widespread addiction. The treaties also resulted in territorial losses, with Britain gaining the Kowloon Peninsula, further expanding its colonial influence in the region. To cover war expenses, China was burdened with heavy indemnities, further crippling its already struggling economy. These humiliating terms reinforced foreign dominance over China and deepened the nation’s decline, fulling resentment and setting the stage for future nationalist movements.

Consequences of the Opium Wars

Economic and Social Collapse

The Opium Wars devastated China’s economy. The outflow of silver further weakened the currency, and the legalisation of opium ensured continued addiction among the population. Many Chinese people, especially in rural areas, suffered as opium consumption led to poverty and social breakdown. The Qing government’s inability to control the trade demonstrated its declining power, leading to increased resistance from its own people.

Foreign Domination and Unequal Treaties

The wars marked the beginning of the “Century of Humiliation” (1839–1949), during which China faced relentless foreign exploitation. Western powers, along with Japan, carved out spheres of influence in China, controlling trade and exerting political pressure. The loss of Hong Kong and other territories underscored China’s diminishing sovereignty.

Rise of Anti-Qing and Anti-Foreign Sentiment

Many Chinese viewed the Qing government as weak and incapable of defending the country. This dissatisfaction fueled uprisings, including the Taiping Rebellion and later the Boxer Rebellion (1899–1901), both of which aimed to expel foreign influence. The humiliation of the Opium Wars contributed to the eventual collapse of the Qing dynasty in 1912 and the rise of nationalist movements seeking to modernise and reclaim China’s independence.

Conclusion: A Lasting Impact

The Opium Wars were a turning point in Chinese history, symbolising the destructive effects of Western imperialism and China’s internal weaknesses. Britain’s aggressive trade policies, coupled with the Qing dynasty’s inability to effectively resist, led to a prolonged period of foreign domination and social decay. However, the legacy of the Opium Wars also played a crucial role in shaping modern China’s drive for sovereignty, reform, and national pride. Today, the wars serve as a reminder of the dangers of economic exploitation and the importance of maintaining national strength in the face of external threats.