Gods of the Sun and War: Exploring Aztec Pantheon and Beliefs

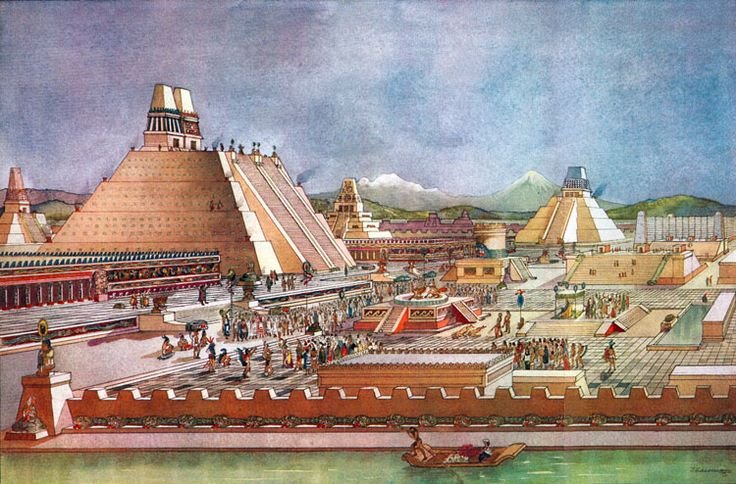

The Aztec civilization (ca. 14th-16th centuries) was characterized by its rich and complex religious and traditional practices, which shaped every aspect of their society. From the grand ceremonies in Tenochtitlán’s towering temples to the intimate daily rituals of commoners, religion and tradition were deeply embedded in their way of life. This article explores these elements in greater detail to illuminate the spiritual and cultural world of the Aztecs.

Aztec belief

At the heart of Aztec religion was the concept of cosmic balance, where the universe was sustained by the interactions of creation, destruction, and renewal. This cyclical view of time and existence informed all their beliefs and practices.

- Creation Myths:

The Aztecs believed they lived in the era of the “Fifth Sun,” created after four previous worlds were destroyed in cataclysmic events. Each sun was linked to a specific element (earth, wind, fire, or water), and the current sun was sustained by human effort and divine sacrifice.

- Sacrifice as Cosmic Duty:

For the Aztecs, human life was not an individual possession but a divine gift that could be returned to the gods to maintain the universe’s balance. This belief justified their practices of offering blood and lives to their deities.

- Duality in Nature:

Aztec thought often paired opposites—light and dark, life and death, male and female—as complementary forces necessary for universal harmony. This duality was reflected in their myths, rituals, and societal roles.

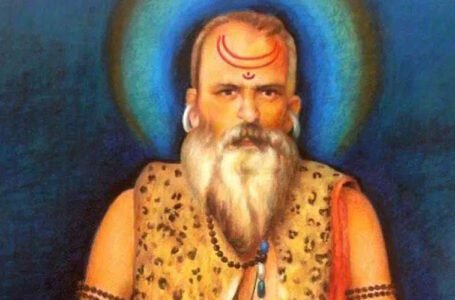

The Aztec Pantheon

The Aztecs worshipped a vast array of deities, each associated with particular elements, phenomena, or human activities. Their gods reflected the complexity of their environment and society.

Major Deities

- Huitzilopochtli (God of the Sun and War):

As the patron deity of Tenochtitlán, Huitzilopochtli was central to Aztec identity. His daily struggle to rise as the sun was believed to require nourishment through human blood.

- Tlaloc (God of Rain and Fertility):

Tlaloc governed the rains and agricultural fertility, crucial to the survival of the agrarian Aztec society. Rituals for Tlaloc included offerings of jade, food, and, at times, child sacrifices to ensure good harvests.

- Quetzalcoatl (Feathered Serpent, God of Knowledge and Creation):

A benevolent figure, Quetzalcoatl was linked to learning, art, and wind. He was also a culture hero, credited with creating humanity in some myths.

- Tezcatlipoca (God of Fate and Chaos):

Known as the “Smoking Mirror,” Tezcatlipoca was a deity of night, sorcery, and destiny. His dual nature made him both a creator and destroyer, embodying life’s uncertainties.

- Coatlicue (Earth Goddess):

Depicted as a terrifying yet nurturing figure, Coatlicue symbolised the Earth’s dual role as the giver and taker of life.

Specialised Deities

The Aztecs also worshiped gods specific to their professions and daily activities:

- Xipe Totec: God of spring, renewal, and agriculture.

- Tlazolteotl: Goddess of purification, sin, and fertility.

- Chalchiuhtlicue: Goddess of rivers, lakes, and fertility, associated with Tlaloc.

Rituals and Religious Practices in Aztec Religion

Rituals were fundamental to Aztec religion, encompassing practices designed to honour the gods, sustain the cosmos, and reinforce social and political structures. The most prominent among these practices were human sacrifices, diverse offerings, and grand festivals. Aztec rituals were performed in sacred spaces, often large temple complexes like the Templo Mayor in Tenochtitlán. These spaces symbolised the connection between the earthly and divine realms, with temples often designed as replicas of mythical mountains or cosmic structures. Underlying all rituals was the Aztecs’ cyclical view of time and belief in the interconnectedness of all realms. They believed that through precise and disciplined rituals, they could ensure the balance of the cosmos, prevent catastrophes, and uphold the cycles of life and death.

Human Sacrifice

The Aztecs believed their gods sustained the universe through their own sacrifices. To repay this divine debt, human offerings were seen as essential to ensure cosmic stability. Victims, often war captives or slaves, were taken to temple pyramids where their hearts were removed by priests using obsidian knives. The hearts were offered to the gods, symbolising the life force required to sustain the sun, rain, and agricultural fertility.

The ceremonies were highly structured and performed during key religious festivals, often on monumental temple sites like the Templo Mayor. While war captives were the primary source of victims, children and voluntary participants were also sacrificed during specific rituals to honour deities such as Tlaloc and Huitzilopochtli.

Offerings

Offerings were central to daily religious practice and grand ceremonies alike. They were acts of devotion, gratitude, and supplication, reflecting the Aztecs’ belief in reciprocity with the gods.

- Material Offerings: These included food, flowers, incense, and valuable items such as gold and jade, often left at altars or buried at temple sites.

- Bloodletting: Self-sacrifice, or auto-sacrifice, was a common practice where individuals, including priests and rulers, offered their own blood by piercing their skin with sharp objects. This was seen as a deeply personal and direct gift to the gods.

- Symbolism: Offerings were tailored to specific gods and their domains. For example, corn and water were common offerings to agricultural deities, while warriors’ remains were dedicated to Huitzilopochtli.

Festivals and Ceremonies

The Aztec calendar, comprising 18 months of 20 days each, was filled with elaborate festivals honouring specific deities and marking agricultural and celestial events.

- Structure of Festivals: Each festival was tied to a deity, combining offerings, dances, music, and sacrifices. Priests led the ceremonies, often accompanied by entire communities participating in processions, feasts, and rituals.

- Major Festivals:

- Tlacaxipehualiztli: Dedicated to Xipe Totec, this festival involved gladiatorial contests and sacrifices of warriors, symbolizing renewal and fertility.

- Panquetzaliztli: Celebrated Huitzilopochtli with large-scale sacrifices, feasting, and theatrical reenactments of mythological events.

- Etzalcualiztli: Honored Tlaloc with rituals to invoke rain, including the sacrifice of children whose tears were believed to bring water from the heavens.

Festivals served not only spiritual purposes but also strengthened community bonds, reinforced the social hierarchy, and showcased the Aztecs’ cultural identity.

The Aztecs were a society deeply woven with religious practices and social rituals that influenced not just their spirituality but their governance, family structures, and daily lives. These traditions reflected a belief in cosmic balance and the integration of spirituality into every aspect of life, guiding everything from political decisions to personal milestones.

Divination and Omens

Divination played a central role in Aztec life, with priests and soothsayers interpreting natural signs and omens to guide both personal and societal decisions. These diviners used a variety of tools to “read” the will of the gods and the forces of nature. Obsidian mirrors, believed to offer a gateway to the divine, were one of the primary instruments used for scrying. In addition, casting maize kernels and inspecting the entrails of sacrificed animals were common methods to foresee the future, predict outcomes, or ensure divine favour for major undertakings such as warfare or agriculture. The Aztecs believed that understanding these omens would help them align their actions with the cosmos and maintain harmony.

Calendar Systems

Two primary calendar systems governed every aspect of Aztec life. The Tonalpohualli was a 260-day ritual calendar closely tied to divination, with each day associated with particular gods, energies, and destinies. It was used for spiritual events, ceremonies, and daily life, allowing individuals to understand when it was the right time for certain actions, such as engaging in war or farming. The second calendar, the Xiuhpohualli, was the 365-day solar calendar that regulated agricultural and civic activities. Organised into 18 months, each consisting of 20 days, this calendar was critical for planting, harvesting, and religious ceremonies that honoured the gods associated with nature and agriculture. Together, these two calendars formed the backbone of Aztec societal order, creating a rhythmic cycle that governed both sacred and secular events.

Life Cycle Rituals

The Aztecs placed great importance on life cycle rituals, marking the key transitions of individuals from birth through death. Birth was considered a sacred event, and newborns were cleansed with water as a symbol of purification. This ceremony was meant to remove any impurities from the child and prepare them to enter the world as pure beings. When it came to marriage, ceremonies were elaborate affairs that united not just two individuals but their families and communities. The marriage ceremony was more than a personal bond; it was a union of cosmic and earthly forces, signified by the tying of the couple’s hands, a symbolic gesture that represented their mutual commitment and connection.

Death was also a major event in Aztec life, with detailed rituals designed to ensure a safe passage to the afterlife. For Aztecs, death was not seen as an end but as a transition to another world, and the nature of one’s death determined their fate in the afterlife. Warriors who died in battle and women who died in childbirth were seen as heroes, and their deaths were celebrated as sacrifices to the gods. These individuals were believed to join the sun’s journey across the sky, a powerful reward for their sacrifices. Those who did not die in battle or childbirth faced a more arduous journey through the underworld, Mictlan, which required endurance and perseverance.

Syncretism and Legacy

After the Spanish conquest in 1521, many of the Aztec’s religious practices were suppressed, but the resilient nature of indigenous traditions led to the blending of Aztec spirituality with Catholicism in a process known as syncretism. This fusion allowed Aztec religious elements to survive, albeit transformed. One of the most enduring examples of this syncretism is the Day of the Dead, a festival that honours the deceased and celebrates the cyclical nature of life. While originally rooted in Aztec traditions of honouring the dead, the event was incorporated into the Catholic calendar, blending indigenous customs with the Catholic observances of All Saints’ and All Souls’ Days.

The merging of these traditions created new forms of religious expression, but at its core, it allowed indigenous people to maintain a sense of cultural identity and spiritual continuity in the face of colonisation. Over time, elements of Aztec traditions became interwoven into the broader Mexican cultural landscape, leaving a legacy that is still evident in festivals, rituals, and daily practices across the country

Conclusion

Aztec religion and traditions were a profound expression of their identity and worldview, emphasising the interconnectedness of life, death, and the divine. Despite centuries of colonial suppression, the spiritual and cultural legacy of the Aztecs continues to resonate in modern Mexico, a testament to their enduring influence on history and humanity.