Cinema and Politics in Post-Independent India: A Complex Interplay

Since gaining independence in 1947, Indian cinema has wielded profound influence over the nation’s political, social, and cultural landscape. It has evolved into a multifaceted medium, reflecting the complexities of Indian society while simultaneously shaping public consciousness. The relationship between cinema and politics is deeply intertwined, highlighting cinema’s role as both a mirror and a moulder of societal values and political ideologies.

Cinema as a Vehicle for Social Change

From its early days, Indian cinema has been a potent tool for addressing societal issues. During the colonial era, films like Bhakt Vidur (1921) used allegory to propagate Gandhian ideals, portraying the Hindu mythological character Vidura as a symbol of nonviolent resistance. This blending of mythology and political commentary laid the groundwork for cinema’s dual role as entertainment and social critique.

Post-independence, cinema became a voice for social reform. Films such as Achhut Kanya (1936) challenged caste discrimination, while Mother India (1957) epitomised the struggles of rural India, symbolising resilience and national pride. These films resonated with the masses, offering both reflection and aspiration.

The 1970s marked the advent of parallel cinema, a movement driven by filmmakers like Satyajit Ray and Shyam Benegal. This genre offered a stark critique of societal inequities, tackling issues like poverty, corruption, and communalism. Films such as Garam Hawa (1974) poignantly depicted the aftermath of Partition, while Ankur (1974) highlighted rural exploitation, showcasing cinema’s ability to illuminate marginalised voices.

In the years following liberalization, cinema began addressing issues like urbanisation, gender equality, and modernity. This shift was not only a reflection of societal transformation but also a response to evolving audience expectations. Films like Chak De! India (2007) emphasised empowerment and collective identity, highlighting cinema’s continued role as a catalyst for change.

Political Commentary and Nation-Building

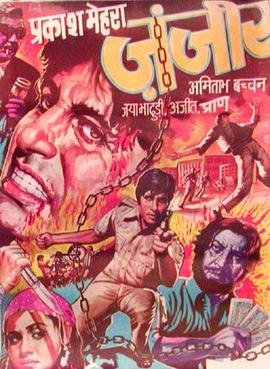

Indian cinema has been a canvas for exploring political ideologies and national identity. The archetype of the “Angry Young Man,” immortalised by Amitabh Bachchan in films like Zanjeer (1973), mirrored public dissatisfaction with systemic failures. This trope underscored the gap between the promises of independence and the lived realities of ordinary citizens.

Regional cinema, particularly in Tamil Nadu, has been instrumental in merging cinematic and political narratives. Film stars like M.G. Ramachandran (MGR) transitioned seamlessly into politics, leveraging their on-screen personas to build political careers. Their films often carried populist messages, creating a feedback loop between reel and real-life heroism. This phenomenon underscores the unique power of cinema to shape political destinies.

The integration of politics and cinema is also evident in the evolution of narratives surrounding nationalism. As noted in resources from institutions like CUH, films serve as critical tools for constructing collective memories. The portrayal of anti-colonial struggles in films like Shaheed (1965) and Lagaan (2001) not only celebrates India’s history but also shapes contemporary understandings of patriotism alism and Cinematic Narratives

Cinema has played a critical role in fostering a sense of nationalism. Benedict Anderson’s concept of “imagined communities” finds resonance here; films serve as cultural artefacts that construct and reinforce collective identities. Historical epics like The Legend of Bhagat Singh (2002) and Chittagong (2012) emphasise stories of resistance and valour, inspiring audiences while providing a cinematic interpretation of historical events.

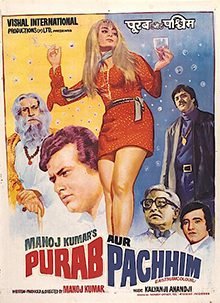

The portrayal of foreign lands and cultures in Indian cinema has also contributed to national identity formation. Films like Purab Aur Paschim (1970) juxtaposed Indian values with Western lifestyles, reinforcing the moral superiority of Indian traditions. This motif was revisited in contemporary films like Swades (2004) and Namastey London (2007), emphasising the resilience of Indian identity in a globalised world.

The rise of Indian diaspora films further expands this discourse. Movies such as Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge (1995) highlight the cultural duality of Indians living abroad, balancing modernity and tradition. As Deepan Boopathy notes, these films serve as a bridge between the homeland and the global Indian identity, cementing cinema’s role in shaping a collective sense of belonging.

Cinema as Cultural Reflection

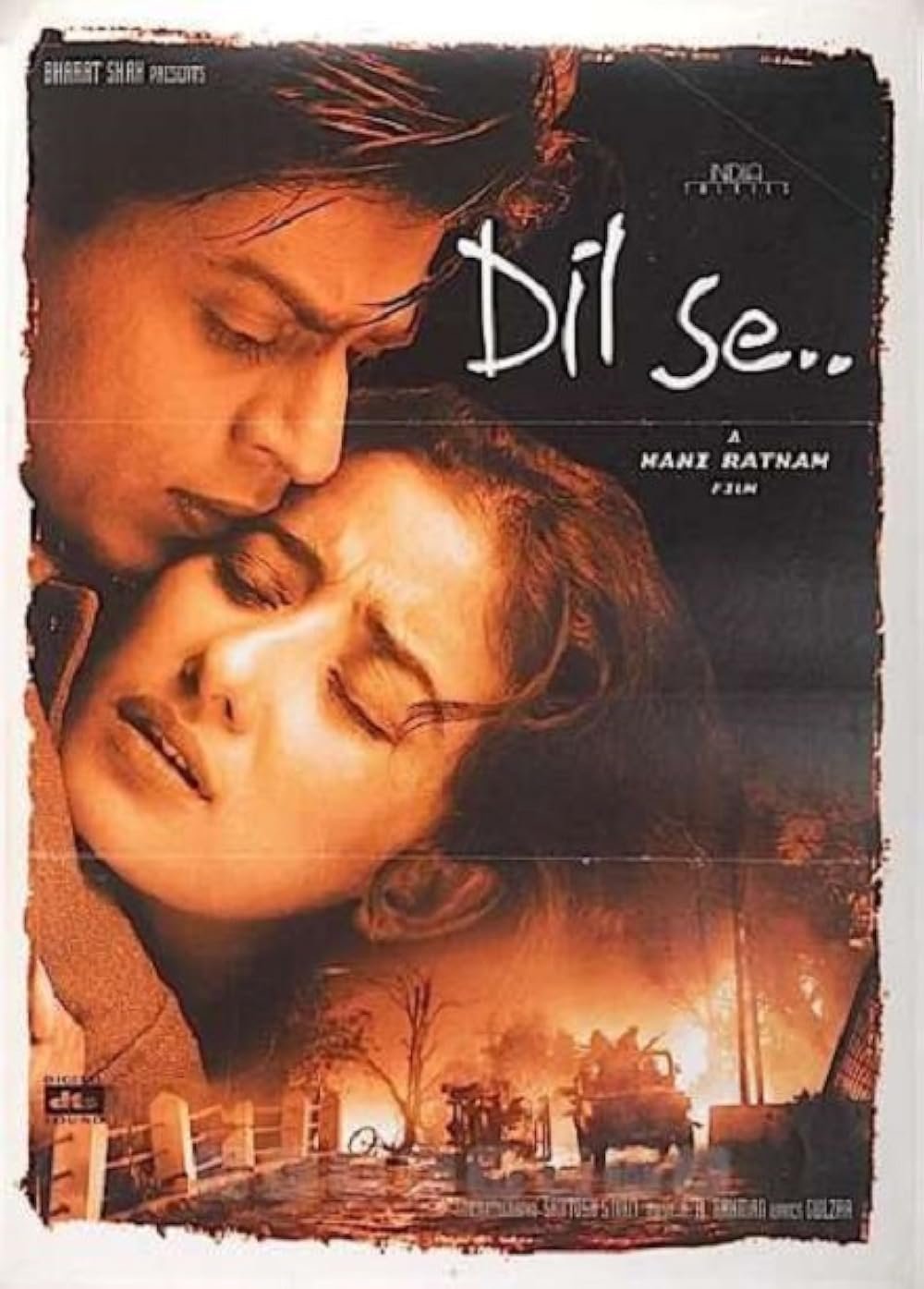

Indian cinema has consistently reflected the nation’s cultural evolution. During the post-liberalisation era of the 1990s, Bollywood narratives began to grapple with themes of modernity versus tradition. Films like Dil Se (1998) and Rang De Basanti (2006) not only mirrored the anxieties of a rapidly changing society but also acted as platforms for youth-driven discourse on politics and ethics.

The rise of multiplexes and digital streaming platforms has further diversified cinematic narratives. High-budget films like Baahubali cater to pan-Indian audiences, while independent cinema explores niche themes such as LGBTQ+ rights (Aligarh, 2016) and gender dynamics (Thappad, 2020). This duality reflects the ongoing negotiation between mainstream aspirations and marginalised identities.

Parallelly, cinema has documented the changing landscape of Indian cities, as highlighted in works by urban theorists. Films like Mumbai Meri Jaan (2008) delve into the urban experience, addressing issues of migration, terrorism, and community resilience.

Historical Films: A Lens on the Past

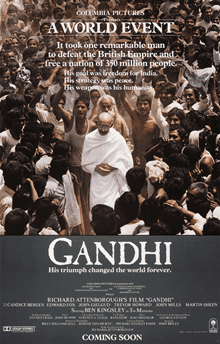

Historical films occupy a significant space in Indian cinema, offering dramatised renditions of pivotal events that resonate deeply with audiences. These films not only entertain but also educate, serving as a bridge between the past and the present. Iconic examples such as Gandhi (1982) and Mangal Pandey: The Rising (2005) have successfully captured the essence of significant historical milestones. Gandhi brought Mahatma Gandhi’s philosophy and role in India’s independence movement to a global audience, while Mangal Pandey delved into the life of a revolutionary whose actions ignited the First War of Independence in 1857. These narratives, however, are not without controversy. They often blur the lines between historical fact and creative fiction, leaving viewers to navigate the interplay of accuracy and dramatisation.

As noted in the Illinois State University study, historical films frequently blend factual elements with fictional embellishments. This blend is often a result of filmmakers’ efforts to make the narratives more compelling and emotionally engaging. While such films provide a visually rich and evocative interpretation of history, they also run the risk of oversimplifying or altering key events to suit narrative needs. For instance, Jodhaa Akbar (2008), a historical drama about Emperor Akbar and his queen Jodhaa, faced criticism for its historical inaccuracies, with historians questioning its portrayal of relationships and events. Similarly, Padmaavat (2018) stirred debates about historical authenticity versus cinematic license, as it drew upon an epic poem rather than verifiable historical records.

This interplay between historical accuracy and creative liberty raises important questions about the role of cinema as a historical medium. Can films serve as legitimate historical sources, or do they merely present an interpretation of history filtered through a contemporary lens? While visual narratives offer an immersive experience, they often prioritise emotional resonance over factual rigor. The selective nature of cinematic storytelling means certain elements are amplified or omitted based on what suits the narrative arc. This approach, while effective for storytelling, complicates cinema’s relationship with history.

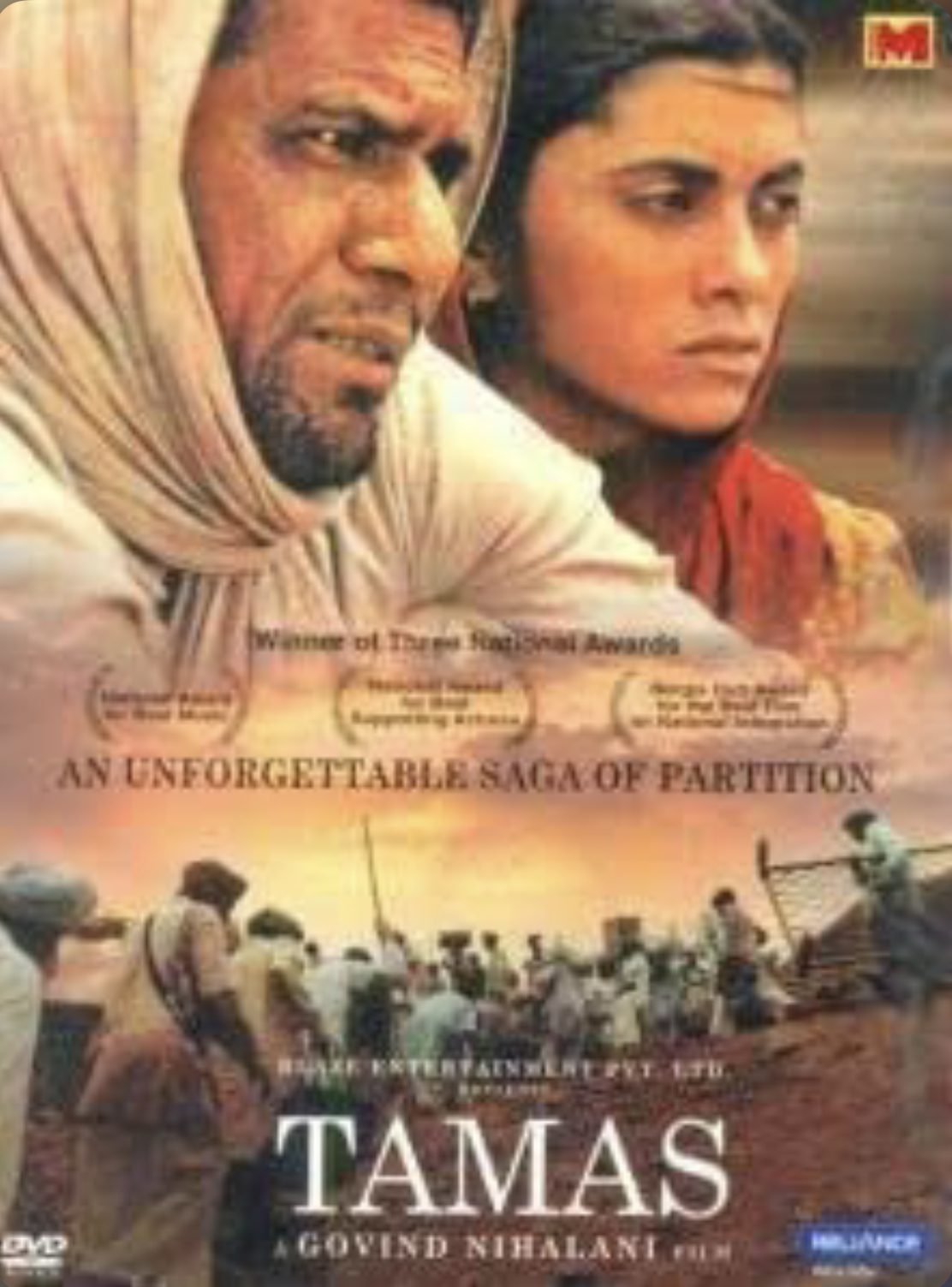

Films like Tamas (1987) and Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar (2000) illustrate this tension. Tamas, a poignant depiction of the Partition, does not claim to provide a comprehensive account of events but instead focuses on the human suffering and communal discord that defined the era. Similarly, Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar highlights the struggles and triumphs of one of India’s foremost social reformers, emphasising his fight against caste discrimination while navigating the challenges of condensing a complex life story into a feature film. These films should therefore be viewed as interpretative rather than definitive accounts, providing a starting point for deeper inquiry rather than conclusive historical documentation.

Furthermore, historical films serve as a medium to engage with the collective memory of a nation. They reinforce or challenge popular narratives and contribute to the formation of national identity. This dynamic is evident in movies like Shaheed (1965), which immortalised Bhagat Singh as a symbol of revolutionary fervour, and The Legend of Bhagat Singh(2002), which offered a more nuanced portrayal of his political ideology. Both films, despite their differences, highlight the enduring appeal of using cinema to celebrate and critique historical figures and events.

The role of historical films is not limited to storytelling but extends to shaping public discourse. They often serve as a cultural touchstone, sparking debates and discussions about the accuracy of historical representation and the ethics of creative liberties. In a nation as diverse as India, where multiple perspectives on history coexist, films provide a platform for these narratives to interact, clash, and evolve. This makes historical films a significant, though complex, site for exploring the past and its relevance to contemporary society.

Parallel Cinema: Experimentation and Realism

Parallel cinema, or “art house” cinema, offers a counter-narrative to mainstream Bollywood. Pioneers like Satyajit Ray and Ritwik Ghatak utilized this medium to delve into the socio-political fabric of India. Ray’s Pather Panchali (1955) and Ghatak’s Meghe Dhaka Tara (1960) explore themes of poverty and displacement, employing a realistic aesthetic that contrasts with Bollywood’s escapism.

This genre has evolved to include filmmakers like Anurag Kashyap, whose films (Gangs of Wasseypur, 2012) offer gritty portrayals of contemporary issues. Parallel cinema’s focus on authenticity and experimentation underscores its role as a critical lens on Indian society.

Global Influence and Diaspora Cinema

Indian cinema’s global reach has amplified its cultural significance. The diaspora’s engagement with Bollywood has created a transnational identity, blending Indian and global sensibilities. Films like Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham (2001) cater to nostalgic diaspora audiences, reinforcing cultural ties while navigating global narratives.

Conversely, the portrayal of India in international films often reflects Western perspectives. While films like Slumdog Millionaire (2008) have garnered acclaim, they also perpetuate stereotypes, highlighting the complex dynamics of cultural representation.

Challenges and Future Directions

Indian cinema faces challenges in balancing commercial imperatives with creative integrity. The dominance of star-driven narratives often sidelines experimental cinema, limiting diverse representation. Additionally, the increasing influence of political ideologies on filmmaking raises concerns about censorship and artistic freedom.

Despite these challenges, the democratisation of filmmaking through digital platforms offers new opportunities. Independent filmmakers now have greater access to resources and audiences, enabling the exploration of untold stories. This shift signals a promising future for Indian cinema as a space for innovation and inclusivity.

Conclusion

The interplay between cinema and politics in India since 1947 exemplifies cinema’s dual role as a reflector and influencer of societal change. As India continues to navigate its complex socio-political landscape, cinema remains a vital medium for articulating collective identities, challenging norms, and inspiring change. From historical epics to contemporary dramas, Indian cinema encapsulates the nation’s spirit, serving as both a chronicler of its past and a beacon for its future.