Vedanta or Uttara Mimansa: The Pinnacle of Hindu Philosophy

The term “Vedanta,” or “End of the Vedas,” represents not only the concluding portion of the Vedic literature but also the supreme object of Vedic knowledge, which is liberating knowledge and the realization of oneself. Unlike most of the other prominent systems of philosophy, which may focus more on ritualism or social commitments, Vedanta is primarily focused on an understanding of the essence of existence, the self (Atman), and the universe (Brahman). It primarily seeks to establish the identity of the Atman and Brahman; Vedanta, thus, describes the innate kinship of the individual among all, contained in the supreme consciousness.

It is a philosophy centred on the knowledge and realization of one’s true nature, moksha (liberation) in this case; indeed, liberation is achieved via knowledge, and knowledge liberates from the cycle of birth and rebirth. The fundamental principles Easterly summarized as “Aham Brahmasmi,” (I am Brahman) and “Tat Tvam Asi” (You are that) express an awareness one with an understanding of one’s unity with the whole universe.

Vedanta provides a comprehensive Kriya and is scattered with suggestions for ponderable contemplation and timeless wisdom on life. It teaches each seeker to rise above worldly enchantment and recognize his inner divinity. The search for wisdom and liberty has played a crucial role in shaping Hindu spirituality and still propels seekers worldwide.

History of Vedanta

The Vedic metaphysical discourses following the Upanishads can be dated back to a time sometime between 1000–500 BCE. Approaching philosophical contemplations beyond the ritualistic basis of the previous Vedic texts, the Upanishads ushered in a new paradigm with a perspective of enlightening works founded on inner wisdom and self-inquiry.

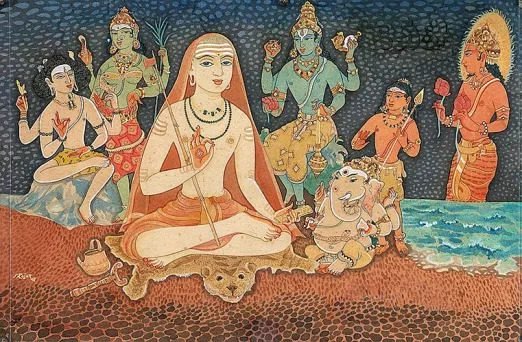

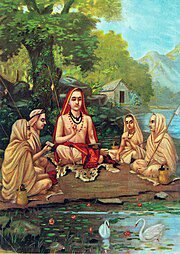

By the period of the 5th to 8th century CE, Vedanta had begun evolving itself into a formal system of thought. The greatest proponent of transforming the stream into a systemic philosophical tradition was Adi Shankaracharya, a philosopher, and saint. Developed on the Brahma Sutras, the work-oriented majestic interpretative cover laid by him reconciled the various interpretations of the Vedantic thought.

Down through the ages, various philosophers such as Ramanuja, Madhva, and Vallabha would greatly expand upon Shankaracharya’s teachings to devise diverse sub-schools of Vedanta, offering various viewpoints on the nature of Brahman and the path to liberation. This particular genre was and is still perhaps somewhere progressively carrying forward till modernity establishing an unprecedented ground of monumental change for the fabric of Hindu personal and collective philosophy. With the entry of Swami Vivekananda and other reformers, Vedanta earned for itself a universal recognition of great esteem that implemented spiritual and ethical values and beliefs.

Today, Vedanta has taken its place as one of the core Hindu philosophies and a great source of inspiration for souls in the world who seek deliverance in their perennial search for the Truth.

Notable Writers and Commentators

Badarayana: Badarayana, the author of the Brahma Sutra, is considered one of the earliest and most famous figures in Vedanta. The Brahma Sutras collect the teachings of the Upanishads and organize them as the basic texts of Vedanta. Badarayana’s work laid the foundation for interpretations in Vedanta, enabling later philosophers to build on his insights.

Adi Shankaracharya: The eighth-century philosopher Adi Shankaracharya is one of the most influential figures in Vedanta. Shankaracharya’s Advaita Vedanta upholds non-duality and holds that Brahman alone is real and the individual soul (Atman) is identical to Brahman. Shankaracharya’s commentaries on the Upanishads, the Bhagavad Gita and the Brahma Sutra are central to Advaita Vedanta, which shaped much of Hindu spiritual thought.

Ramanuja: Ramanuja, a 12th-century philosopher, founded Vishishtadvaita (qualified non-dualism) Vedanta, a difficult Shankaracharya’s view of pure non-dualism. Ramanuja believed that even as the person’s soul is wonderful from Brahman, it remains intimately related to it, just like waves in an ocean. His works, especially his remark on the Brahma Sutras, offered an interpretation of Vedanta that emphasizes devotion (bhakti) as a means of knowing Brahman.

Madhva: The 13th-century philosopher Madhva developed the Dvaita (dualism) school of Vedanta, which clearly distinguishes between Brahman and the individual soul. According to Madhva, there is an eternal separation between the soul of Brahman and the material world. His teachings emphasized the worship of Vishnu and provided the basis for a dualistic approach to spiritual practice in Hinduism.

Vallabha and Nimbarka: Both Vallabha and Nimbarka gave different views of Vedanta. Vallabha proposed Shuddhadvaita (pure non-dualism), asserting that the universe is the true manifestation of Brahman. Nimbarka introduced Dvaitadvaita (dualistic non-dualism) which holds that soul and Brahman are separate but inherently related. Their teachings fertilized the soil of Vedanta and added variety and depth to its philosophy.

Verses and Teachings

Vedanta, rooted in the Upanishads, the Bhagavad Gita, and the Brahma Sutras (Prasthanatrayi), centres on the nature of the self (Atman) and its unity with the universal consciousness (Brahman).

- Aham Brahmasmi (Brihadaranyaka Upanishad): “I am the Brahman.” This phrase reflects the non-dual nature of existence and emphasizes that the individual soul (atman) is not separate but identical to the ultimate reality, Brahman This realization is the basis of self-realisation and the end of ignorance.

- Tat Tvam Asi (Chandogya Upanishad): “You are That.” This verse expresses that the essence of the individual is one with the universal essence, Brahman. Its teaching is used to awaken the understanding of the interconnectedness between self and the universe, erasing perceived separateness.

- Sarvam Khalvidam Brahma (Chandogya Upanishad): “All this is Brahman.” This verse expands on the idea that everything in the universe, seen or unseen, is an expression of Brahman, highlighting that multiplicity is only an appearance and, at the core, all is one.

- Brahma Satyam, Jagan Mithya, Jivo Brahmaiva Na Aparah (Advaita Vedanta): “Brahman alone is real, the world is an illusion, and the individual soul is Brahman.” This teaching in Advaita Vedanta explains the illusory nature of the world and the oneness of Atman and Brahman, freeing one from material attachments.

- Anando Brahma (Taittiriya Upanishad): “Bliss is Brahman.” Vedanta teaches that true happiness or bliss is inherent in Brahman itself, not in external pursuits. This verse encourages seekers to realize this inner bliss through self-realization.

Legacy and Influence of Vedanta

Vedanta’s interests concerning interconnections dwelling in each of the existing entities have widely affected several philosophic movements, within and beyond Hinduism. Its teachings initiated the Bhakti Movement, harnessing much of the theological support for devotional operator procedures.

Vedanta schools of Brahman and Atman had an immediate influence on both Indian and Western philosophy woke its landmark thinkers Ralph Waldo Emerson, Aldous Huxley, and Carl Jung. Those beats of Vedanta resound through Indian art, literature, and music, illustrating and establishing the subject of self-realization.

Various Indian dance forms like Bharatanatyam exemplify non-dualism. The dancers express the nature of the union of the individual identity with universal consciousness. The influence of Vedanta in Indian literature has appeared prominently in the works of such estimated poets as Tulsidas and Kabir, for their verses exquisitely encapsulate the deepest philosophy of Vedanta.

Vedanta has gained immense popularity thanks to the likes of Swami Vivekananda, who propounded Vedantic principles with great vigour during the Parliament of World’s Religions held in Chicago in 1893. Vivekananda delivered the message of Vedanta marked by unity, universal tolerance, and spirituality, and his message made an unprecedented impact throughout the world in the formation of modern spiritual movements in the West.

Learnings from Vedanta

Vedanta proposes that all beings are manifestations of the one ultimate reality, Brahman and cultivates compassion, oneness, and empathy from the belief that people can see themselves in others and will thus respond in loving kindness and understanding. Vedanta emphasizes the tenderness of self-examination (Atma-vichara) and the search for one’s true nature. The liberation (moksha) from the raucous cycle of birth and death will physicalize on the overcoming of the transient aspects of the ego and realization of unity with Brahman.

Vedanta teaches us to free ourselves from material desires and gratification from external sources and to realize that true happiness comes from within. Vairagya-the renunciation of the agitation allows one to delve into matters of the spirit and be unaffected by materialistic diversions and pleasures. In the quest for self-realization, meditation and mindfulness have not surprisingly factored in their importance.

Such disciplines pacify the workings of the mind and thus allow the individual to transcend his self-centred desires and reside in the sphere of peace through an intimate reconnecting with the reality of his being. The message propagated by Vedanta about oneness and non-duality has cultivated an ambience of acceptance and sensitivity to the coexistence of differences. Vedanta, through the recognition that all religious paths, within and beyond the realm of the apparent, lead to the same truth, has nurtured a spirit of respect for the various spiritual practices, cultivating harmony amidst a multi-ethnic society.

Conclusion

Vedanta explains entirely the self, the universe, and the path to salvation. It is Brahman, the supreme essence, and the unity of the individual soul (atman) with this supreme consciousness. This very idea of oneness strengthens an individual in rising above physical limitations, thus, unfolding their hidden divinity. Vedanta has been enriched by Shankaracharya, Ramanuja, and Madhva. Each of them was able to provide a fresh fill on how Atman relates to Brahman and influences Indian culture, spirituality, and philosophy in its prime. Shankara’s non-dualism (Advaita) affirmed the identity of Atman with Brahman. With Ramanuja’s qualified non-dualism (Vishishtadvaita), the emphasis was on one’s relationship with God.

Madhva’s dualism lays stress on the difference between the soul and God. In today’s complicated world, Vedanta advocates unity, compassion, and consciousness, which serve as an illumination to guide. It imparts peace to the inner self and reminds everybody of their approach to one being.

The path of Vedanta may be followed through knowledge (jnana), devotion (bhakti), or action (karma); it eternally imparts timeless wisdom that transcends cultural borders. This universal philosophy of Vedanta compels one to act as an observer, recognize one’s higher self, and live a peaceful life. Vedanta light is the eternal guiding spirit for all those who seek it worldwide.