The Serpent’s Embrace: Ophiolatry in Early India

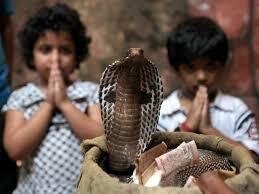

India, often portrayed as the land of snake charmers and serpent worshippers, is steeped in centuries-old traditions surrounding serpents that go beyond mere exoticism. This cultural affinity, known as ophiolatry or snake worship, is not a relic of the past but a tradition woven into the spiritual and social fabric of India. This article delves into the complex relationship between humans and serpents in ancient India, exploring historical texts, artistic representations, sacred spaces, and contemporary practices to uncover the depth of this ancient tradition.

Understanding Ophiolatry: A Multidimensional Perspective

Snake worship in India is frequently misinterpreted when viewed through the singular lens of Hinduism, Buddhism, or Jainism. In reality, ophiolatry is an intricate cultural phenomenon that includes indigenous and folk beliefs, where snakes are seen not merely as animals but as powerful spiritual beings. The Vedas, Puranas, and various epics depict serpents as creatures both feared and revered, embodying life-giving forces such as water, fertility, and protection, while also symbolising death and the unknown.

The essence of ophiolatry lies in this duality. While people fear the venomous power of snakes, they also view them with reverence for their perceived control over nature’s primal forces. This interplay of awe and fear has fostered a cultural reverence for serpents as deities, guardians, and symbols of cosmic energy.

Serpent Symbolism in Ancient Texts and Rituals

In the Vedic period, serpents held a prominent place in spiritual beliefs, seen as intermediaries bridging the gap between humans and the divine. They symbolised powerful elemental forces like water and rain, essential for life and prosperity. Serpents were believed to possess supernatural abilities, making them both feared and revered. Their worship was deeply intertwined with prayers for fertility, agricultural abundance, and protection from natural calamities, all of which were vital to early agrarian societies. The Atharva Veda, one of the four sacred Vedas, includes hymns specifically dedicated to appeasing snakes, recognising both their dangerous potential and their role as protectors of the land.

As Indian mythology evolved, the Puranas further enriched the lore surrounding serpents, portraying them as nagas—semi-divine beings with immense power and wisdom. These nagas, often described as half-human and half-serpent, were thought to reside in sacred, hidden realms beneath the earth, where they governed natural elements and protected hidden treasures. As rulers of these mystical subterranean worlds, nagas were believed to control natural phenomena, especially those related to water bodies and fertility. They were considered protectors and, in some traditions, divine ancestors capable of blessing their devotees. The Skanda Purana, a significant text in Hindu mythology, provides detailed descriptions of rituals and offerings to honour the nagas. These rites, performed with great devotion, were believed to secure the goodwill of the nagas, invoking blessings for fertility, prosperity, and the overall well-being of the community.

The Serpent in Art and Archaeology: Tracing Cultural Roots

Artistic representations of serpents in India provide a window into the profound reverence and awe with which these creatures were regarded. From the time of the Indus Valley Civilisation through the Gupta period, serpent motifs appear across a spectrum of artistic forms, including intricate carvings, paintings, reliefs, and grand sculptures. Archaeologists have unearthed a wide range of serpent artifacts in ancient sites, from modest snake figurines to the grand statues of nagarajas, or serpent kings, which emphasise serpents’ roles as both regal and protective figures in society. These artifacts and symbols underscore the belief in serpents as powerful forces in nature, as guardians, and as deities that command respect.

The nagaraja iconography is especially compelling in its symbolic richness. These images often depict gods, saints, or heroes being sheltered by multi-headed serpents, such as in the iconic Naga Muchalinda motif. This powerful visual represents Buddha protected by the serpent king Muchalinda, who shields him from a storm, embodying the serpent’s divine protection and cosmic power. Similarly, sculptures of Hindu deities like Vishnu resting on the multi-headed Shesha, or Shiva with Vasuki coiled around his neck, illustrate the intimate bond between serpents and the divine. These motifs convey the complex qualities attributed to serpents—they are not only feared for their venomous potential but are also respected and revered for their protective nature, wisdom, and transformative powers.

The Sacred Landscapes: Sarppakavus and Snake Groves of Kerala

In Kerala, the practice of ophiolatry, or snake worship, finds a distinct and beautiful expression in sacred snake groves, locally known as sarppakavus. These lush groves, often dense with a variety of flora and fauna, are more than just patches of preserved wilderness; they are revered as the abodes of serpent deities and other protective spirits. Passed down through generations, sarppakavus are carefully preserved by local families who believe these groves safeguard their well-being and bring blessings to the community. These sacred spaces reflect a harmonious blend of spirituality and ecology, where both the snakes and the land they inhabit are venerated. Disturbing or harming the snakes, plants, or even the natural terrain within these groves is thought to invoke divine displeasure, which can bring misfortune to those involved.

One of the most significant serpent-worship sites in Kerala is the Mannarasala Temple, a renowned pilgrimage centre dedicated to serpent gods. Uniquely, this temple is maintained by a traditional Brahmin priestess, who upholds centuries-old rituals and customs. During festivals like Ayilyam, the temple attracts thousands of devotees who come to seek blessings from the serpent deities, performing rituals and offerings in their honour. The festivities include an array of ancient chants, songs, and dances that are performed to invoke the presence and favour of the serpent deities. Through these rituals, worshippers hope for good health, prosperity, fertility, and protection from harm.

Key Figures in Naga Lore: The Symbolism of Serpent Deities

The pantheon of Hindu serpent deities is diverse and filled with figures that embody both the benevolent and malevolent aspects of serpents. These serpent deities serve not only as protectors but as cosmic forces influencing the natural world. Below are twelve prominent serpent deities in Hindu mythology, each representing unique qualities and powers:

- Shesha: Known as the “Eternal Serpent,” Shesha symbolises infinity and stability, representing the cosmic balance upon which the universe rests.

- Vasuki: Revered as the great naga who allowed himself to be used as a churning rope during the Samudra Manthan, Vasuki embodies the spirit of sacrifice and cosmic balance.

- Takshaka: The Naga King known for his role in the Mahabharata, Takshaka represents vengeance and justice, often invoked in rituals seeking protection.

- Manasa: The goddess of fertility and protector against snake bites, Manasa is a popular deity in Bengal, worshipped by those seeking protection and health.

- Kaliya: A venomous serpent subdued by Krishna, Kaliya represents the taming of nature’s dangers and the victory of good over evil.

- Adi Shesha: The primordial serpent, believed to support the planets on his hoods, represents cosmic stability and continuity.

- Ulupi: A Naga princess married to the warrior Arjuna, Ulupi exemplifies loyalty and the nurturing aspects of serpent mythology.

- Padma: The Naga King associated with wisdom and dharma, Padma is revered for his role in maintaining cosmic order.

- Karkotaka: Known for his role in the story of Nala and Damayanti, Karkotaka represents transformation and rebirth.

- Shankhapala: A compassionate naga protector associated with dharma and cosmic order.

- Astika: Known as the saviour of the nagas, who halted the snake sacrifice by Janamejaya, Astika embodies the principles of reconciliation and harmony.

- Dhritarashtra: A powerful Naga king mentioned in the Puranas, Dhritarashtra symbolises strength and protection.

Rituals and Festivals: Honoring the Divine Serpents

The worship of serpent deities often takes place during festivals, with Naga Panchami being one of the most widely observed. Celebrated across India, this festival sees devotees offering milk and prayers to serpent idols, seeking protection from snake bites and other dangers. Devotees also make offerings to the serpent gods for blessings of fertility and prosperity.

In Kerala’s temples, elaborate rituals include the singing of Pulluvan pattu, hymns performed to honour the snake deities, while women draw colourful serpent patterns as offerings. In Assam and Bengal, Manasa Puja is a significant event, celebrated with songs, dances, and recitations of the Manasamangal Kavya, which narrates tales of the goddess Manasa’s benevolence and protective powers.

Ophiolatry Beyond India: The Universal Symbolism of Serpents

The worship of serpents extends beyond India, reflecting a universal human connection to these enigmatic creatures. Ancient civilisations across the world have revered serpents, seeing them as symbols of life, death, and rebirth:

- Mesopotamia: The Sumerians and Babylonians revered serpents as symbols of immortality, with their skin-shedding seen as a metaphor for rebirth.

- Egypt: In Egyptian mythology, the serpent Apep represented chaos, while Wadjet, the cobra goddess, was a symbol of protection and royalty.

- Greece: The Greek god Asclepius, associated with healing, was often depicted with a serpent-entwined staff, symbolizing medicine and life’s cyclical nature.

These global perspectives underscore the common themes of protection, fertility, and transformation associated with serpent worship, illustrating humanity’s shared reverence for the power and mystery of serpents.

The Legacy of Serpent Worship in Contemporary India

In modern India, the ancient practice of snake worship continues to flourish, with Naga Panchami celebrated annually across many regions. On this day, devotees offer milk, flowers, and prayers to snake idols and images, seeking blessings for protection, prosperity, and the well-being of their families. The festival serves as a reminder of the enduring reverence for these creatures and the deep-seated cultural connection they represent. In regions like Kerala, traditional serpent groves known as sarppakavus are carefully preserved by families, functioning as sacred spaces where ecology and spirituality intertwine. These groves, rich in biodiversity and home to numerous medicinal plants, underscore the ecological wisdom embedded in the practice of ophiolatry, bridging ancient rituals with modern conservation values.

Contemporary popular culture in India further brings this legacy to life, with television shows, folklore, and Bollywood films frequently exploring the mythical ichchadhari naag (shape-shifting serpent) who can transform between human and serpent forms. These stories captivate the public imagination, weaving ancient lore into present-day narratives that resonate with audiences of all ages. The shape-shifting nagas embody a mix of mystique, power, and reverence, and their presence in entertainment highlights the fascination with serpents’ ability to transcend human limitations, symbolising both divine protection and mortal danger.

Conclusion: The Timeless Legacy of Ophiolatry

Ophiolatry in India represents a fascinating, intricate bond between humanity and nature, where serpents embody both the primal fear of the unknown and a profound reverence for life-giving forces. Rooted in mythology, sacred texts, and everyday practices, this tradition reveals a cultural acknowledgment of life’s dualities—creation and destruction, danger and protection, wisdom and mystery. Serpent worship goes beyond mere superstition; it is a recognition of humanity’s place within a larger cosmic order, acknowledging that the powers of nature demand both respect and understanding.

Modern India continues to honor this heritage through festivals like Naga Panchami and the upkeep of sarppakavus in Kerala, which are not only sacred spaces but ecological treasures that preserve medicinal plants and biodiversity. These rituals link communities to their ancestors, blending past and present in celebrations that invite people to reflect on the natural world’s beauty and dangers. The enduring appeal of serpent deities like Manasa, Sheshanaga, and Vasuki also speaks to an India that cherishes its ancient wisdom, passing down stories and rituals that reinforce the importance of ecological balance and respect for all life forms.

Today, the serpent remains an enduring symbol of awe, woven through both traditional rites and popular culture, where shape-shifting nagas and mystical cobras capture the public imagination. This living tradition of ophiolatry reminds us of our profound connection to nature, embodying the timeless understanding that humanity must coexist harmoniously with the natural world. In every ritual, myth, and sacred site, ophiolatry is a testament to an enduring respect for life’s mysteries—a powerful cultural legacy that transcends generations and offers a deeply rooted sense of place and purpose within the vast tapestry of existence.