MOIDAMS OF ASSAM: Where the Royal Spirits Slumber

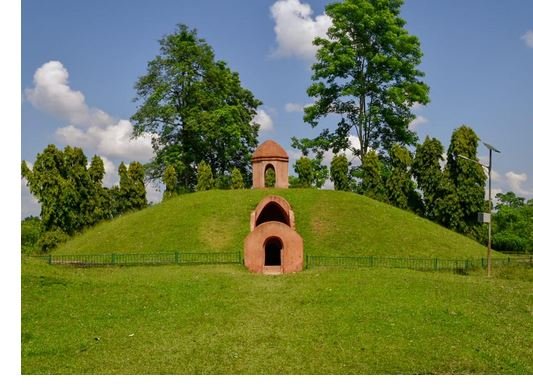

Draped with a history of desolation for decades, the northeastern region of India will finally have a cherry on the cake with its first UNESCO cultural site in the form of Moidams of Assam which are a necropolis of royal spirits resting in their abodes carving out a legacy over the stretch of six centuries. These moidams are the burial system belonging to the Ahom Dynasty who reigned over Assam from 13th to 19th centuries, surpassing their rivals, i.e., the Mughals.

Historically, the Ahom dynasty traces its origin to Great Tai (Tai-Yai) group of people from China who migrated in 1215 CE from Mong-Mao and entered through the Patkai pass into the Upper Assam region of Brahmaputra Valley under the founder Chau-lung Siu-ka-pha or Chao-pha or Swargadeo (Lord of the heaven). Cheraideo or Chetamdoi meaning ‘a dazzling city above the mountain’ became the first capital of the Ahom Dynasty. Over the six hundred reigning years, the Ahoms expanded their kingdom to engulf the whole of Brahmaputra Valley and played a crucial role in bringing political, cultural and economic stability to the region of northeast. They are also credited for bringing together the various ethnic tribes under one administrative umbrella, popularising the policy of matrimonial alliances, and socio-cultural assimilation which eventually expedited the formation of a hybrid nationality which later came to be known as Assamese.

Brilliant successors like Suhungmung, Suklengmung, Pratap Singha, Gadadhar Singha, Rudra Singha, Shiva Singha, Pramatta Singha, and Rajeswar Singha established a strong state in the Brahmaputra valley, shielding it from Islamic rulers, including the Mughals which established generations of peace and prosperity, allowing the multiethnic Assamese culture to thrive.

Although the Ahoms are known for their various secular as well as religious architectural undertakings, the Moidams miraculously standout being extraordinarily unique in style bearing the specimen of a foreign origin. Moidam, which are the burial mounds of not only the Kings but also the Queens and Nobles, is derived from the Tai word Phrang-Mai-Dam or Mai-Tam. Phrang-Mai means to put into the grave and Dam refers to the spirit of the dead.

DISCOVERY AND EXCAVATION

There were times when children unknowingly played on the royal burials, and cows accidentally fell into burial pits and encroaches, especially British, carelessly encroached the ground for tea plantations. The villagers who trace their ancestry to the Ahoms have ever since worshipped these moidams.

Over time, encroachments have been removed, and sugarcane crops cleared. Though a total of 386 Moidams are explored from Tipam Hills in Upper Assam’s Tinsukia district to Nagaon in Central Assam, Charaideo is home to 90 moidams forming a necropolis of Royal Regals which are considered accurate representations of Ahom dynasty burial traditions. Historical records indicate it houses the burial mounds of most Tai Ahom kings. The first Ahom king, Chau-lung Siu-ka-pha, was buried at Charaideo observing all Tai-Ahom religious rites and rituals which established the tradition of burying Tai-Ahom kings, queens, princes, and princesses at Charaideo. This reflects how both female and male royalty were honoured equally. Over the centuries, the site became a revered and sacred place. The Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) and the Directorate of Archaeology of the Assam government jointly maintain the site and its 754.52-hectare buffer zone, which includes historical tanks from the Ahom period, tea gardens, estates, and a few sparsely populated villages.

The earliest sketch of a Moidam’s ground plan was published in the journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal in June 1848. It was drawn by Sergeant C. Clayton, who supervised the excavation of a Moidam in 1840 at the request of Captain T. Brody, the Principal Assistant Commissioner of Assam at the time. Clayton and his team discovered rings, a silver toothpick case, ear ornaments, goblets, platters, and a small gold lime container, which were later purchased by Mr. Bedford. Archival reports indicate that in 1905, a Moidam was excavated under the supervision of several Ahom princesses, but no further information is documented.

In 1951, the ASI declared large Moidams in Charaideo as protected sites, leading to their designation as national property in 1975. In 2015, the adjacent Moidams were protected by the Directorate of Archaeology and the Indigenous and Tribal Faith and Culture Department of the Assam government.

Most of the burial mounds remain unexplored. Excavations by the ASI between 2000 and 2003 of Moidam No.2 revealed more architectural details and recovered human skulls, terracotta plaques, decorated ivory pieces, gold pendants and wooden objects. One wooden object is likely the shaft of a dish-on-stand (sarai), designed in the shape of a stambha (pillar). An ivory panel depicts a mythical dragon, the Ahom royal insignia, along with intricate engravings of an elephant, peacock, and floral motifs. Other artefacts found included pieces of copper objects fitted to wood, an iron hook, an iron pin, small ivory decorative art objects, round ivory buttons, cowries, gold pendants, and a few lead cannon balls.

The accurate date or the individual whom this Moidam shelters is challenging to determine due to the lack of documentation. However, based on the artefacts, the nature of the brick structures, and literary references from the Buranjees regarding Ahom cremation practices after adopting Hinduism, the construction of this Moidam can be attributed to the first half of the 18th century CE.

A DIVE INTO THE ARCHITECTURE

A Maidam consisted of five major features- a vaulted chamber known as Chaw-chali (temple-like open pavilion) meant for annual offerings atop a hemispherical earthen covering (Ga-Moidam) of mud mound layers of bricks, Garvha (underground chamber or pit), a narrow strip of open land with cobblestone edging encircling the mound and a perfect octagonal or polygonal boundary toe-wall (Garh) reinforcing the base entered through an arched gateway on the west side. They are found as single units, double units, and even clusters dotted across a wooded landscape that also sustains water bodies.

A Moidam varied in size from a small mound which did not comprise of all the features to a twenty metres high hillock depending on the resources, power and status of the person buried. Over the years, the exterior of the mound would be covered with a layer of vegetation transforming the burial into a billowing picturesque.

Initially, the vaults were constructed using solid wooden poles and beams but were replaced with stone and brick ones since the reign of King Rudra Singha (CE 1696-1714) and his successors. According to the Chronicles of Charng-rung Phukan (Chang-rung Phukanar Buranjee), the bricks and stones of the Moidams were bonded with a mortar made from a mix of lime (limestone and snail shells), black pulses, resin, hemp, molasses, and fish. The superstructure was built using boulders of various sizes, broken stones and brick pieces, while the substructure was constructed with large stone slabs.

Excavations revealed that the remains of the deceased were placed on a centrally raised platform after rituals lasting from six months to two years. The Ahom chronicles provide a glimpse of the paraphernalia the Ahom kings were buried with, including their treasures, everyday items like clothes, ornaments, royal insignia, items made of wood, ivory, or iron, gold pendants, ceramic ware, weapons, silver utensils, quilts and pillows embroidered with gold thread, precious stones, cowrie shells, and even human beings from the Luk-kha-khun clan, were buried with the king. Therefore a large number of valuables and attendants, whether alive or dead, were buried with royalty and dignitaries. However, the practice of burying people alive was banned by King Rudra Singha. These burials served as treasure caches for robbers and plunderers, the Mughals, British and even the native residents.

The Mound Builders

In addition to enumerating the materials used in constructing a Moidam, the Changrung Phukan also records the number of labourers, the duration of the work, the votive offerings made, and the rituals followed during the cremation of the royals with great resplendence and panoply, indicating their hierarchical status.

According to Ahom chronicles, only individuals from the Ghraphalia and Likhurakhan khel (khel were groups each consisting of one to five thousand people who were allocated specific tasks) were allowed to bury the bodies of kings and queens. The Ahom Buranjees (Chronicles) recountals that a coffin, called Rung-dang, was made from a specific type of timber known as Uriam (Bescoffia javanica) which was transported to the burial site in a Kekora dola (a type of Assamese litter) exclusively by people from Ghraphalia and Likhurakhan khel. The large vault beneath the hemispherical earthen mound, known as Kareng-Rung-dang, housed the coffin, which was placed in an east-west orientation. Only the Lukhukhans were permitted to enter the Kareng-Rung-dang. After placing the body inside, they sealed the vault’s door with boulders in clay mortar.

At Charaideo, there was a specific road laid for transporting the bodies, known as Sa-nia-ali (Sa meaning dead body, nia meaning carry, and ali refers to path or road), and a particular tank for the ritualistic bathing of the bodies, known as Sa-Dhua-Pukhuri (Sa meaning dead body, dhua- bath, and pukhuri- tank).

The Ahom kings designated a special officer, Changrung Phukan, for the construction and maintenance of all civil works, including the Royal Moidams. He was among the nine most highest-ranking Phukans in total. Additionally, special officers called Moidam Phukans and a guard group known as the Moidamiya were appointed to protect and maintain the Moidams.

SEMBLANCE WITH SIMILAR STRUCTURES

The Moidams of Cheradoi show certain similarities with the funerary rituals of entombing the deceased Royals in tombs of ancient China and the pyramids of Egypt who also buried their kings, queens and pharaohs with their respective paraphernalia.

As many Ahoms later adopted Buddhism as well as Hinduism, they began cremating their dead. Nevertheless, the burial tradition continues to be practised by the priestly sections of the Ahoms, such as the Mo-chai, Mo-hung, and Mo-plang, as well as the Chao-dang (royal bodyguards) clan. Many people revere Cheraideo as a sacred and pious place where shoes are removed at the gates before entering the site and prayers are offered. The Ahoms also observe two annual rituals to venerate the dead namely Tarpan, celebrated in December and the festival of Me-Dam-Me-Phi (worshipping of ancestors) which is celebrated on 31 January.

Oral Tales that hold the lost Moidams

When researching the Ahom Dynasty, former ASI director Dr. KC Nauriyal acknowledges the significance of oral history, despite its potential challenges in authentication through excavation. These stories, passed down over generations, can offer valuable insights for unravelling new Moidams.

According to one such oral lore, about 10 Moidams were vandalised by the army of Mir Jumla II, a prominent governor under Aurangzeb who invaded Assam in 1662. However, pinpointing their exact locations is difficult. Villagers also believe that the Moidam of the first king, Siu-Ka-Pha, is located in the buffer zone. Yet, oral traditions are not definitive or authentic. Therefore the dossier submitted to UNESCO does not take note of this.

Forever igniting their faith in the royal ancestral spirits whom they glorified as ‘Gods on Earth’ laying in a deep slumber under the eternal sky, the Ahoms’s legacy has traversed beyond their six hundred years of rule and carried forward by their successors who still worship and conserve the royal burial landscape symptomatic of Tai Ahoms.