THE CAVE OF ALTAMIRA: A Hunted, Neglected and an Extraordinary Espial

While hunting down the origin of artistic expression in homo sapiens, one can barely overlook the once forsaken oldest work of palaeolithic paintings beehived in the Cave of Altamira. The cave was inhabited for more than a millennia spanning over Gravettian (25000 BCE – c. 20000 BCE), Solutrean (19000 BCE – c. 15000 BCE) and Magdalenian (15000 BCE – c. 10000 BCE) periods. Created over a timespan of 20,000 years, these upper palaeolithic paintings stand as a testimony to the earliest evidence of cave engravings, development of human cognitive psyche and sophistication in 3D perspective in artistic field.

Situated in Santillana del Mar in northern Spain, 30 km west of the port city of Santander in Cantabria region, the cave with its swirling galleries and crouched chambers is approximately 270 metres and nestles various remains that provide an insight into the prehistoric lifestyle of Stone Age. The physiographic region of “Cantabrian Croniche” is home to a number of caves representing a cultural society- Peña de Candamo, Tito Bustillo, Covaciella, Llonín, El Pindal, Chufín, Hornos de la Peña, Las Monedas, La Pasiega, Las Chimeneas, El Castillo, El Pendo, La Garma, Covalanas, Santimamiñe, Ekain and Altxerri- clubbed together known as ‘The Cave Of Altamira and Palaeolithic Cave Art of Northern Spain’.

Designated as a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1985, the cave is known for its exemplifying distinct art and enriching history. Discovered in the mid nineteenth century as the cave entrance was covered by a rockfall, the impeccable engravings have gone a long way in revitalising our lens through which we contemplate prehistoric art and culture.

History in a hunt and a young girl’s eyecatch

The cave was first hunt down by a hunter named Modesto Cubillas in 1868 who then informed the nobleman Marcelino Sanz de Sautola who initially didn’t show much interest and visited the cave only in 1876 after which he returned with sheer disappointment defiling the art as mere absurd symbols and carvings. However, after visiting the 1878 Universal Exhibition in Paris and noticing the carved bone pieces similar to those he had found in the cave, he realised their noteworthiness and began the excavations in 1879 in partnership with Juan Vilanova y Piera, an archeologist from the University of Madrid.

The entrance was a store of objects made of flint, bone, horn as well as colourants, fauna and shells that assisted in the dating of the cave paintings. And it was his 8 year old little daughter, Maria who accompanied him to the caves one day and pinpointed to the paintings of bison on the ceiling of one of the chambers.

Sanz de Sautola, subsequently published his “Notes on some prehistoric objects in the Santander region” (Breves apuntes sobre algunos objetos prehistóricos de la provincia de Santander) in 1880 which was not met with appreciation but rather the authenticity of the paintings was questioned by French scholars who could not find any similarity with the cave paintings unearthed in France and thus condemning the art as ‘modern forgery’. Moreover, it sparked controversial debates within the members of the church who hitherto were absorbed in the prevailing belief that such sophisticated and impressive artworks could not possibly have been created by prehistoric humans, who were often dismissed as primitive “cavemen.” The very notion that these paintings may have been the work of both men and women was not even entertained at the time.

It was only with the advent of the nineteenth century, with the publication of Les cavernes ornées de dessins. La grotte d’Altamira, Espagne. «Mea culpa» d’un sceptique (“The caves decorated with drawings. The cave of Altamira, Spain. «Mea culpa» of a sceptical”) in 1902 by E. de Cartailach, a French prehistorian, that the cave gained prominence in international prehistoric research.

In 1903, H. Alcalde del Río further carried out the excavations and unearthed two successive layers: one from the Upper Solutrean and the other from the Lower Magdalenian, both of which form a part of the Palaeolithic Period. These findings were corroborated by Hugo Obermaier’s excavations in 1924 and 1925, as well as by J. González Echegaray and L. G. Freeman in 1980 and 1981, which revealed a more complex archaeological record. Studies and C14-AMS dating conducted in 2006 exhibited eight distinct levels of human habitation from middle Magdalenian to the Gravettian period over a millennia. In 2008, researchers using uranium-thorium dating established that the cave paintings were likely created over a period of 20,000 years. A subsequent study in 2012 verified that at least 10,000 years separated different paintings within the caves.

The cave of Altamira thrived as the first place in the world where parietal art belonging to the Upper Palaeolithic was found and was subsequently followed by the discovery of similar caves in Lascaux, France.

THE CAVE AND ITS ENGRAVINGS

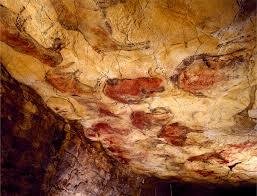

The cave is compartmentalised into three sections namely: the entrance, the great polychrome room and the gallery. The entrance forms the habitation of the ancient humans where numerous stone tools, animal bones, ash from fireplaces, flint objects such as knives, axes, flint fragments, were found in layers of sediments. The polychrome or great room, known for its kaleidoscopic paintings, is located in the cave’s interior where natural light does not reach. The entrance and the polychrome room together form the great hall, but due to the cave’s narrow gallery, there is limited space for large areas, aside from the main chamber. The cave concludes with a narrow gallery that is difficult to access, yet it also shelters Palaeolithic paintings and engravings.

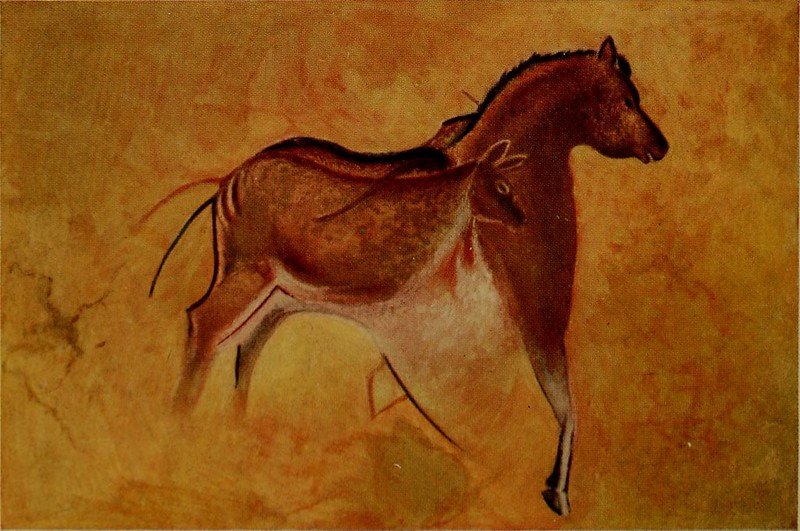

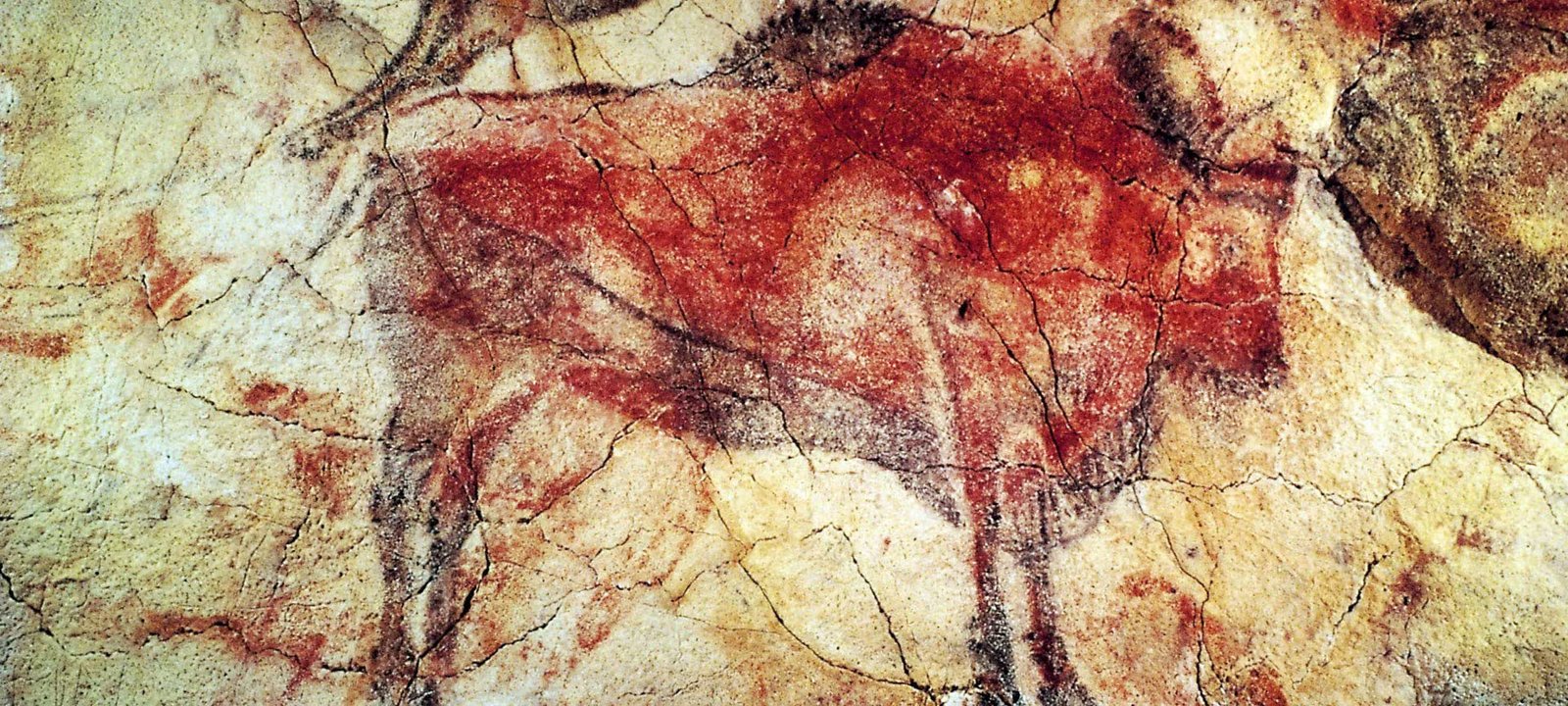

The paintings contained in Altamira are mostly drawn on the ceiling ranging from animals to hands and symbols predominant in the polychrome room which is stupefying given the height of the lateral chamber, for instance, varies from 3.8 feet to 8.7 feet which meant that the artists had to kneel down, paint above their head while unable to see the whole ceiling at once. On the right side of the roof of this chamber, horses, bison, positive and negative impressions of human hands, abstract shapes and symbols, and a series of dots are largely sketched with charcoal. The representations of deer dominate these paintings. On the natural protuberances of the rocks, ‘masks’ have also been outlined by drawing eyes and mouth.

The artwork in the cave is a fusion of both engraving and painting. The technique involved engraving the wall with flint objects and then black outlining using charcoal followed by colouring the figures in a synthesis of yellow and red, sometimes in violet shades too. The details such as hair were executed by charcoal pencils while features like eyes, nose and horns were engraved in bumps and cracks purposefully to provide volume to the illustration and give a three dimensional perspective to the art.

The largest representation is of a doe which measures approximately 8.2 feet (2.5 metres) while the most exotic paintings of the cave constitute the 25 vibrantly coloured figures of horses, deer and bison. Charcoal to create black lines and grounded hematite for red ochre was used to stroke the depictions.

This particular area of the cave is adorned with several other carvings, including a number of figures that resemble humans, various imprints and stencils of hands. Moreover, the cave’s other passageways feature a diverse collection of figures rendered in black paint and carved into the surfaces belonging to the lower Magdalenian. The Magdalenian period exhibits a mosaic of artwork- ranging from depictions of horses, aurochs, bison, goats, deer, human faces, and various signs.

The Ceiling Of THE RED HORSES

The oldest layer of artwork on the principal ceiling exhibits creatures depicted in red, along with carved symbols, hand imprints, and sequences of dots. Eleven sizable red illustrations of animals, dominated by horses and each measuring between 1.5 and 1.8 metres in length, were once scattered extensively over a significant portion of the ceiling. These exceptional figures do not incorporate any of the ceiling’s contours or natural features.

Adjacent to the Hall of the Paintings is a very tight passage embellished with red markings. One particular design is made up of four unevenly shaped ovals with internal divisions. Additionally, another design, which stretches 3 metres and consists of lengthy bands of red filled with parallel lines intersected by smaller lines, is positioned beneath a section of rock that is out of reach.

THE LAST BISON

The most recent artwork at Altamira, as identified and established by carbon dating, is the monochrome bison, which dates to approximately 13,130 +/- 120 years before present. This piece of art demonstrates an artistic skill and execution of a refined level, featuring a persnickety application of charcoal and diligent smudging techniques to achieve shading.

Given that the cave entrance collapsed shortly after the creation of this bison painting, it is enthralling to speculate how the artistic evolution of this sacred space might have persisted if the site had remained accessible. The maturity evident in the final known work suggests the possibility of further artistic progression and the continued development of the Magdalenian cultural tradition within the Altamira cave complex.

A PAIR OF PALAEOLITHIC AIRBRUSH

A set of airbrush tools were also found in the Altamira cave, which were initially mistaken for pendants by Hermilio Alcalde del Río. These tools were made from segments of bird bones and were most likely used to apply red liquid paint. The bone pieces were arranged in such a manner that allowed for the paint to be sprayed outwards when air was blown through one end. While the exact dating of these artefacts is unclear due to a lack of stratigraphic context, their discovery provides insight into the sophisticated techniques employed by the Palaeolithic inhabitants of the Altamira cave.

A speculative association with religious rituals

While some experts point to a possibility that the paintings may have been associated with ritual contexts, such as shaman-led trances to connect with the mysterious spiritual realm, which reflects the cultural complexity and symbolic significance of these Palaeolithic artworks, many researchers remain uncertain about the real purpose and motive behind the creation of these paintings due to lack of precise dating owing to the limited stratigraphic context. But the cave paintings at Altamira were not simply the result of survival-focused cultures, but rather of thriving communities that had the leisure time and resources to engage in sophisticated artistic expression.

ALTAMIRA TODAY: Conservation, a museum and a replica

Altamira cave is currently closed to the public to preserve its condition. Initially, the cave’s entrance collapse helped maintain a stable climate, protecting the paintings. However, once discovered, external air began to alter the cave’s humidity and temperature. Additionally, the 20th-century construction of walls and pathways to accommodate large numbers of visitors further impacted the paintings, deteriorated by the presence of people. To address these issues, measures were implemented between 1997 and 2001. In 2002, a comprehensive conservation plan was instituted by the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC), and since 2011, an international committee of experts has been evaluating the possibility of allowing limited visitor access without compromising the paintings’ preservation.

Although the original cave remains off-limits, a detailed facsimile has been created for visitors in 2001. The Altamira Museum also houses a permanent collection of artefacts from Altamira and nearby caves.

Nevertheless, the cave of Altamira forms a quintessential and earliest example of palimpsest art created over the stretch of thousands of years providing a glimpse of the intricacies of Magdalenian art. It entails symbolism, realism, absolutism and a natural use of third dimensional perspective, unique to this prehistoric work of art.