The Spiritual Journey of Adi Shankaracharya: Uniting India with Vedanta

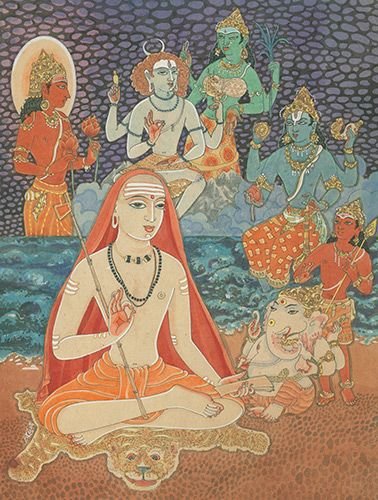

Adi Shankaracharya, a revered Indian philosopher and theologian, stands as a colossal figure in the history of Indian spirituality. His teachings on Advaita Vedanta have transcended time, continuing to influence thinkers and seekers worldwide.

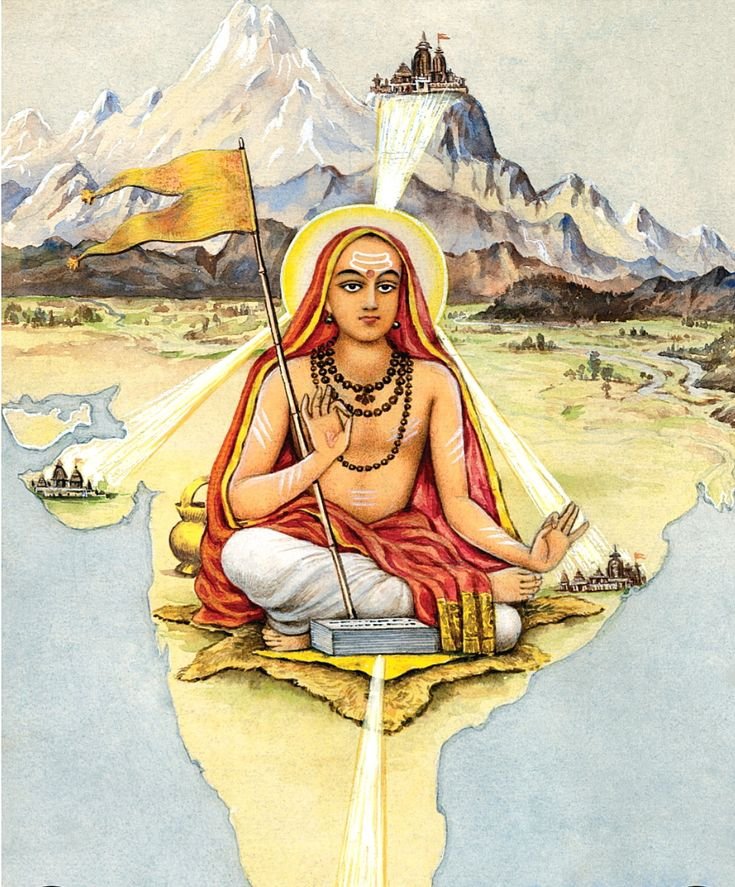

Born in Kerala in the 8th century CE, Shankaracharya showed an early inclination towards spirituality. He renounced worldly life at a young age and became a disciple of Govinda Bhagavatpada, who taught him the essence of the Vedas and Upanishads. Shankaracharya’s most significant contribution was the establishment of the four Mathas (monasteries) in India’s cardinal directions—Sringeri, Dwarka, Puri, and Jyotirmath—which played a pivotal role in preserving and propagating Sanatana Dharma. He also authored several texts elucidating Advaita Vedanta, including commentaries on the Brahma Sutras, Upanishads, and the Bhagavad Gita.

Shankaracharya’s legacy lies in his unification of diverse spiritual practices under the umbrella of Advaita Vedanta. His philosophical works continue to be studied for their profound insights into the nature of reality and self-realisation.

The four Mathas established by Adi Shankaracharya

Sringeri Sharada Peetham in Karnataka: Dedicated to Goddess Saraswati, it is considered the first of the four Mathas. It has been a centre of learning and spirituality, with a lineage of gurus dating back to Shankaracharya himself.

Dwarka Sharada Peetham in Gujarat: Located on the western coast, this Matha is associated with Lord Krishna and plays a crucial role in preserving the Dwaita tradition of Vedanta.

Govardhana Matha in Puri, Odisha: This eastern Matha is linked with Lord Jagannath and is responsible for maintaining the Rig Veda tradition.

Jyotir Math in Uttarakhand: Situated in the north, this Matha focuses on the Atharva Veda and has been instrumental in promoting Shankaracharya’s teachings in the Himalayan region. Each Matha has its own head monk, known as Shankaracharya, who is regarded as a spiritual leader and authority on Advaita Vedanta.

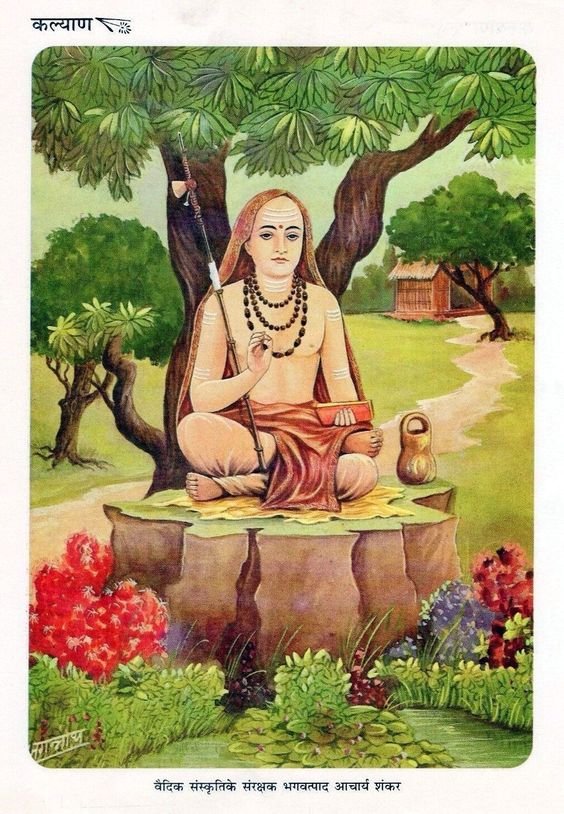

Adi Shankaracharya, also known as Shankara Bhagavatpada, was born in Kaladi, Kerala, around 788 CE. He was a prodigious child with a deep interest in spirituality and philosophy. By the age of eight, he had already mastered the Vedas and decided to take up Sannyasa (renunciation), despite his mother’s reluctance.

Shankaracharya then travelled across India, studying under various teachers and engaging in philosophical debates. His primary guru was Govinda Bhagavatpada, who taught him the essence of Advaita Vedanta—interpretation of the Vedas that emphasises the unity of the individual soul (Atman) with the ultimate reality (Brahman).

Throughout his life, Shankaracharya engaged in spiritual discourses, debates, and authored numerous works that clarified and systematised the principles of Advaita Vedanta. His teachings and writings helped revive Hinduism at a time when it was declining due to the rise of Buddhism and Jainism.

Shankaracharya is also credited with organising the Hindu monks under the institution of the Mathas and establishing the Dashanami monastic order. He attained Mahasamadhi (the act of consciously leaving one’s body at death) at a young age, leaving behind a rich spiritual legacy that continues to inspire millions.

Adi Shankaracharya was a prolific writer, and his works form the core of Advaita Vedanta literature. Some of his notable works include:

Viveka (Discrimination): The ability to distinguish between the eternal and the transient, recognizing the Atman as the only reality.

Vairagya (Dispassion): Developing detachment from material possessions and desires to focus on spiritual growth.

Shad-Sampat (Six Virtues): Cultivating inner qualities such as self-control, patience, withdrawal from sensory objects, endurance, faith, and concentration.

Mumukshutva (Desire for Liberation): Having a strong yearning for liberation from the cycle of birth and death.

Sadhana Chatushtaya (Fourfold Qualifications): Preparing oneself through practices like moral living, purity of thought, devotion, and meditation.

Guru’s Guidance: Seeking a knowledgeable and experienced guru for proper direction on the spiritual path.

Bhashyas (Commentaries): Shankaracharya wrote extensive commentaries on the Brahma Sutras, the principal Upanishads, and the Bhagavad Gita, which are considered authoritative texts on Advaita Vedanta.

Prakaranas (Philosophical Treatises): He authored several independent treatises like ‘Vivekachudamani’ (Crest Jewel of Discrimination), ‘Atma Bodha’ (Self-Knowledge), and ‘Aparokshanubhuti’ (Direct Experience).

Stotras (Hymns): Shankaracharya composed numerous hymns in praise of various deities, including ‘Bhaja Govindam’, ‘Soundarya Lahari’, and ‘Kanakadhara Stotram’.

Upadeshas (Instructional Works): He also wrote instructional texts for disciples and seekers, such as ‘Upadesha Sahasri’.

These works collectively contribute to the understanding of Advaita philosophy and offer guidance for spiritual practice and realisation.

‘Vivekachudamani,’ or ‘Crest Jewel of Discrimination,’ is a spiritual text attributed to Adi Shankaracharya that expounds on the philosophy of non-dualism (Advaita Vedanta). The essence of the text is to guide seekers on the path to enlightenment by discriminating between the real and the unreal.

Key teachings of ‘Vivekachudamani’ include:

The importance of discerning the eternal Atman (self) from the transient body and mind.

The realisation that Brahman (the ultimate reality) is the only truth, and the world is an illusion (Maya).

The need for a guru for proper guidance on the spiritual path.

The practice of virtues such as self-control, patience, and detachment to attain self-realisation.

The text ultimately leads the seeker towards liberation (Moksha) by understanding their true nature as non-different from Brahman. Meditation is a central practice in Shankaracharya’s teachings for achieving self-realisation. It serves as a tool for the mind to focus and attain a state of inner stillness, where one can experience the true nature of the self (Atman) as non-different from the ultimate reality (Brahman).

Shankaracharya emphasised Dhyana (meditation) as a means to Withdraw the senses from external objects. Cultivate inner peace and clarity. Dissolve the ego and individual identity. Realise the oneness of Atman with Brahman.

Meditating on the question “Who am I?” to discern the true self from the body and mind. Chanting sacred syllables or phrases to focus the mind and connect with the divine. Focusing on a divine form or concept to steady the mind and deepen one’s spiritual understanding. Intense and continuous contemplation on the teachings of Vedanta to internalise and realise their truth. These techniques are designed to quiet the mind, sharpen concentration, and ultimately lead to the realisation of one’s true nature as Brahman.

In Advaita meditation, several mantras are commonly used to focus the mind and facilitate a deeper spiritual connection. Some of these include:

Om: The primal sound representing the ultimate reality, Brahman.

So’ham: Meaning “I am That,” signifying the identity of the self with the universe.

Tat Tvam Asi: A Mahavakya from the Chandogya Upanishad, meaning “Thou art That,” affirming the unity of Atman and Brahman.

Aham Brahmasmi: Another Mahavakya from the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad, meaning “I am Brahman,” expressing the non-dual nature of the self.

These mantras are often repeated during meditation to help still the mind and realise the oneness of the individual self with the universal self.

By following these guidelines, mantra meditation becomes a powerful tool for self-inquiry and realisation in the Advaita tradition.

Shankaracharya’s views on mantra meditation:

From ‘Vivekachudamani’:

“The mind should be made to rest in the self after making it free of all connections, by turning away from all attachments through the repetition of the mantra and meditation on its meaning.” (Verse 362)

From ‘Aparokshanubhuti’:

“Through the practice of the repetition of the mantra (Japa), which leads to the disappearance of all other thoughts, and through meditation, the mind becomes one-pointed.” (Verse 119)

Adi Shankaracharya stands as a towering figure of Indian philosophy, revered not only for his profound wisdom but also for his role as an exemplary teacher. His life’s work was dedicated to the propagation of Advaita Vedanta, the non-dualistic school of thought that emphasises the oneness of the individual soul (Atman) with the ultimate reality (Brahman). As a teacher, Shankaracharya was unparalleled in his ability to distil complex metaphysical concepts into accessible teachings, guiding countless seekers towards the path of self-realisation. His compassionate approach, coupled with an unwavering commitment to truth, enabled him to connect deeply with his disciples, imparting knowledge that transcended mere intellectual understanding. Through his seminal texts such as Vivekachudamani and Aparokshanubhuti, Shankaracharya laid down practical steps for spiritual growth, emphasising discrimination, dispassion, and meditation as key practices. His legacy endures through these timeless works, continuing to illuminate the path for those yearning for spiritual liberation. In essence, Shankaracharya’s teachings serve as a beacon of light, leading aspirants from the darkness of ignorance to the dawn of enlightenment.