Essences of the Past: Perfumery in Medieval Europe

Perfume has enchanted humanity for centuries, weaving its aromatic magic through the tapestry of history. From the opulent courts of medieval Europe to the bustling markets of the Middle East, the story of perfume is as rich and diverse as the fragrances themselves.

Perfumery finds its origins intertwined with ancient civilizations, where fragrant oils and incense played integral roles in religious rituals and everyday life. From the sacred perfumes of ancient Egypt to the aromatic offerings of the Greeks and Romans, scent held deep cultural significance.

Yet, it was during the Middle Ages that perfume truly came into its own, thanks in large part to the cultural exchange facilitated by the Crusades. These military expeditions, launched by Christian Europe to reclaim the Holy Land from Muslim rule, brought European soldiers into contact with the opulent lifestyle of the Middle Eastern elite. The Crusaders encountered a culture steeped in the luxurious allure of silk and perfume. In the bustling markets and opulent courts of the Levant, fragrance was not merely a commodity but a hallmark of refinement and status.

While some European pilgrims may have initially viewed the “decadent” lifestyle of the Middle Eastern elite with skepticism, they couldn’t resist its allure. Despite their religious fervor, they found themselves drawn to the exotic perfumes that permeated the air, returning home with these luxury items as tangible souvenirs of their travels. This exchange marked the beginning of a profound cultural interchange that would shape the trajectory of perfumery in medieval Europe. Venice, with its strategic position as a maritime trade hub, emerged as the epicenter of perfumery during this period.

In addition to the imported perfumes, Crusaders brought back a treasure trove of aromatic herbs, spices, and essential oils from the East. The city’s bustling markets became a melting pot of fragrances, with spices like camphor, nutmeg, and pepper mingling with traditional floral perfumes. These fragrant commodities, prized for their practical uses as well as their pleasing scents, found their way into European households. From lavender to thyme, these aromatic treasures not only served medicinal purposes but also imbued people and their clothes with delightful fragrances, masking the odors of daily life.

Contrary to modern notions, de-odorants were not a necessity in medieval Europe. The natural fibers of clothing, coupled with regular exposure to fresh air and woodsmoke, helped mitigate the need for artificial scent-masking products. Moreover, the prevalence of bathing, a practice often overlooked in popular portrayals of the Middle Ages, further contributed to personal hygiene and cleanliness.

During this era, there arose a growing awareness of the importance of hygiene. Cleanliness and, consequently, the use of perfume became significant concerns during the Middle Ages. At elaborate banquets, hosts would present bowls of scented water for guests to cleanse their hands, given that eating with fingers was customary. Wealthier women of the time favored fragrances like lavender and orange blossom, often concealing flowers under their garments and using small sachets filled with perfumed powder in their laundry.

Additionally, bathing became a cherished ritual. Aristocrats practiced bathing at home in large vats crafted from metal, stone, or wood, where spices were infused into the water. Commoners frequented public baths that offered hot, aromatic baths for a nominal fee. These baths served as social hubs where men and women mingled, enjoying moments of relaxation. Following the bath, the indulgence could continue as four-poster beds were available for visitors to luxuriate in delightful company.

Arabian perfumes brought with them not only exotic scents but also sophisticated perfumery techniques. From distillation methods to blending practices, European perfumers eagerly adopted these new approaches, enriching their repertoire of fragrances. Innovations in perfumery techniques further propelled the evolution of fragrance during the Middle Ages. Salerno, Italy, emerged as a center of experimentation, paving the way for the creation of alcohol-based perfumes like Queen of Hungary Water. This blend, crafted from alcohol and rosemary, achieved remarkable popularity. It was applied to the body to ward off infections, and some individuals even consumed it to further experience its exceptional benefits. As international trade flourished, perfumes flowed freely between the Arab world and Europe, enriching the olfactory landscape of both regions.

Perfume houses emerged in medieval Europe as the demand for exotic scents and aromatic blends grew among the nobility and wealthy merchants. Perfume houses were primarily in urban centers, where skilled artisans and traders congregated to create and distribute luxury goods. Cities such as Venice, Florence, and Paris became renowned hubs for perfume craftsmanship, attracting talent from across the continent.

These perfume houses served as centers of innovation, where master perfumers meticulously crafted unique blends using a diverse array of ingredients sourced from distant lands. Spices, herbs, flowers, and resins were carefully selected and combined to produce captivating aromas that captivated the senses.

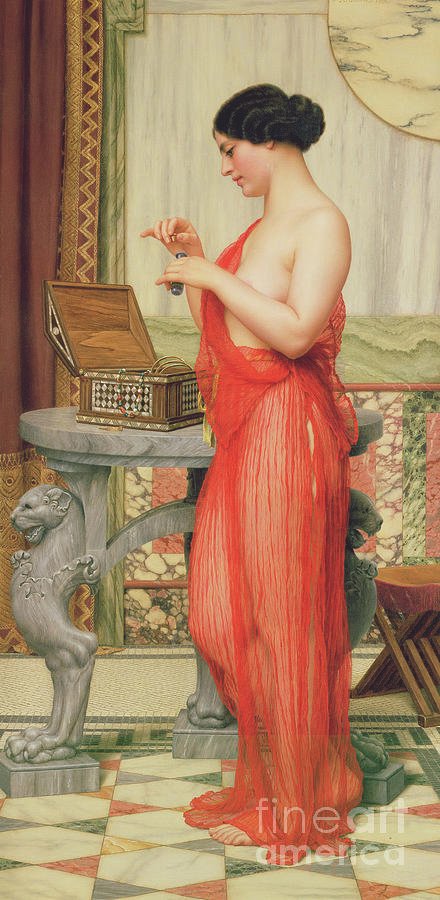

The patrons of these perfume houses were predominantly the nobility and aristocracy, who sought to distinguish themselves with exclusive scents that reflected their status and sophistication. Perfumes were not merely seen as a means to mask odors but as symbols of wealth, taste, and social standing.

Medieval perfume houses also played a crucial role in preserving and disseminating knowledge about fragrance-making techniques. Master perfumers passed down their expertise through apprenticeships and guilds, ensuring the continuity of craftsmanship across generations.

Furthermore, these perfume houses fostered a culture of luxury and refinement, where elaborate rituals and customs surrounded the use of fragrances. Perfumes were worn not only on the body but also infused into clothing, linens, and personal belongings, imbuing every aspect of daily life with an aura of elegance and allure.

As the medieval period progressed, the influence of perfume houses continued to expand, shaping the olfactory landscape of Europe and contributing to the flourishing of arts and culture. However, the decline of the Roman Empire in the 5th century ushered in a period of stagnation in Western perfumery. With the rise of Christianity as the dominant religion, perfume fell out of favor due to its association with pagan traditions. The religious condemnation of perfume as a symbol of excess and immorality further contributed to its decline in the Western world.

Yet, despite these setbacks, perfumery persisted, albeit primarily for its medicinal properties. Monks, renowned for their knowledge of botany and pharmaceutical care, cultivated aromatic plants in abbey gardens, utilizing them in various remedies and aromatic compositions. With the outbreak of the plague in 1347, the therapeutic function of perfume gained renewed significance, with aromatherapy being employed to combat the pandemic.

Thus, perfumery underwent a remarkable transformation, evolving from a symbol of luxury to an essential aspect of daily life. As trade routes expanded and cultures intermingled, perfumes became a conduit for cross-cultural exchange, leaving an indelible mark on the history of fragrance.

During the Renaissance, spanning the 14th to the 16th centuries, perfume emerged as a pivotal aspect of European culture, especially among the nobility. Amidst the complexities of personal hygiene, which often involved elaborate bathing rituals requiring copious amounts of water and time, perfume became a popular alternative to mask body odor. The widespread apprehension regarding water as a potential carrier of disease further fueled the preference for fragrances over bathing.

Amidst the grim backdrop of a plague epidemic, a dread of bathing gradually took hold. Public baths were shuttered, and personal hygiene routines dwindled to a halt. There was a widespread apprehension that water might penetrate the body, facilitating the spread of disease. Consequently, bathing frequency declined sharply. Societal emphasis shifted towards outward appearance as a marker of status and affluence, overshadowing concerns for cleanliness. By the 16th century, bathing became sporadic, often limited to a cursory washing of select body parts. The practice of bathing declined, replaced by superficial cleansing rituals supplemented by fragrant essences. Instead of thorough cleansing, hygiene practices involved rubbing the skin with cloths infused with aromatic substances. Legend even suggests that King Louis XIV of France indulged in a bath only once a year.

This era witnessed an immense flourishing trend of perfumery, particularly favoring robust and intoxicating scents that could effectively conceal other odors. Wealthy nobles indulged in fragrances infused with musk, amber, jasmine, tuberose, and other exotic essences. Perfume was used to conceal the unpleasant odors emanating from poorly washed bodies. These odors were so potent and offensive that highly concentrated and intense scented concoctions were crafted. Animal-derived scents like musk and amber were particularly favored for their strong fragrance and perceived aphrodisiac qualities. Additionally, fragrant botanical ingredients such as jasmine and tuberose found widespread use.

In this era of olfactory camouflage, the perfumed glove emerged as a notable innovation, manufactured in Grasse. This newfound enthusiasm spurred the establishment of a formalized professional guild. The Glovers-Perfumers secured a monopoly on perfume distribution, supplanting the roles of apothecaries and druggists. Grasse, in France, emerged as the epicenter of European perfumery during this time.

Perfume pervaded every facet of life, being applied not only to bodies but also to wigs, clothing, food, and even tobacco. Animals were not exempt from aromatic treatment, with pets and exotic birds often being perfumed. Within households, the pervasive presence of fragrance was evident, with aristocrats adorning cushions with dried flowers and employing scented tablets and sprays to mask unpleasant smells. The courtly milieu was awash with a plethora of fragrances, with the wealthiest individuals changing their scent daily.

The age of exploration, spearheaded by figures like Christopher Columbus, Ferdinand Magellan, and Vasco de Gama, played a pivotal role in shaping the world of perfumery. Their voyages to distant lands introduced Europeans to a myriad of exotic plants and flowers, including cocoa, vanilla, cardamom, tobacco, and pepper. These newfound botanical treasures enriched the repertoire of perfumers, paving the way for the creation of exclusive fragrances that captured the imagination of the elite.

The advent of formalized perfumery regulations can be traced back to Venice in 1555, marking the beginning of an era of perfumed craftsmanship. Italians, renowned for their expertise, pioneered the creation of perfumed gloves, with recipes like “peau d’Espagne,” blending tanned leather with fragrant ingredients. The French Corporation of Perfumed Glove-Makers, established in 1656, further solidified France’s emergence as a perfumery powerhouse, perpetuating the legacy of perfumed luxury.

France, following Italy’s lead, witnessed a surge in perfumery as artisans flocked to Paris, drawn by the city’s burgeoning reputation as a fragrance capital. Royal patronage, notably by figures like François I and Catherine de’ Medici, elevated perfumery to new heights, with renowned perfumers like René the Florentin leaving an indelible mark on the industry. The French aristocracy, epitomized by Louis XIV and his court, embraced perfume as an essential element of their lavish lifestyles, adorning not only their bodies but also their surroundings with fragrant essences.

In the midst of prevailing fears of disease, perfume served a dual purpose as both a cosmetic and a therapeutic agent. The pomander, prevalent in the Middle Ages, was commonly worn by the affluent as a defense against various maladies. Over time, this aromatic object gave way to alternative vessels such as the acorn, a diminutive scented sachet that gained popularity in the 17th century. During times of plague, physicians donned large, impermeable coats to shield themselves from contaminated air. Their faces were concealed behind masks adorned with elongated beaks, filled with herbs aimed at combating noxious and harmful odors.

Perfume purified the body and established a barrier against foul smells. Medical practitioners of the era regarded fragrant ingredients, derived from both animals and plants, as potent remedies. Scented waters were concocted as decoctions, ingested to cleanse the blood and organs of impurities. Ambroise Paré, a renowned surgeon in the service of the king, devised “pots with plants,” specialized baths designed for therapeutic purposes.

In conclusion, perfume’s journey through history reflects its enduring allure and cultural significance, from ancient civilizations to the medieval and Renaissance periods. The Middle Ages saw a profound exchange of fragrances and perfumery techniques between Europe and the Middle East, catalyzing a renaissance in scent craftsmanship. Perfume houses emerged as bastions of innovation, crafting exquisite blends that adorned the nobility and aristocracy with refinement and sophistication.

During the Renaissance, perfume experienced a golden age characterized by a proliferation of fragrances and heightened appreciation for their transformative power. From opulent courts to bustling cities, perfume permeated daily life. As we reflect on perfume’s rich history, we are reminded of its enduring legacy as a symbol of luxury, elegance, healing and sensory delight, inviting us to immerse ourselves in its intoxicating embrace.