The Emperor who loved writing Plays: a Glimpse of Harsha’s Literary Legacy

Harsha, the illustrious king of the Pushyabhuti dynasty, stands as a monumental figure etched in the annals of Indian history. Born in 590 CE in the formidable kingdom of Sthanvishvara, which would later become Thanesar, Haryana, Harsha ascended to the throne in 606 CE. His reign, spanning from northern to northwestern India, saw the zenith of power and the establishment of Kannauj as his imperial capital. Beyond the military triumphs and setbacks, Harsha’s enduring legacy lies in the cultural richness and intellectual vibrancy that thrived under his rule. The peace and prosperity he ushered in made his court a center of cosmopolitanism, attracting scholars, artists, and religious luminaries from far and wide. This introduction unfolds the saga of a grand king whose influence transcended borders and whose imprint on history remains indelible.

Beyond the battlefield, Harsha’s legacy endures in the realm of literature, where he skillfully wove narratives that resonate with timeless themes, inviting readers to unravel the intricate tapestry of his creative genius. Renowned for his literary prowess, he is widely credited as the author of three Sanskrit plays – Ratnavali, Nagananda, and Priyadarsika. These literary treasures not only showcase Harsha’s mastery over language and dramatic composition but also provide profound insights into the cultural and artistic milieu of his time. This article delves into the lesser-explored facets of Harsha’s life, shedding light on his remarkable literary contributions and inviting a deeper understanding of the grand king’s enduring legacy.

Biography of Harsha:

Harshavardhana, Maharajadhiraja of the Pushyabhuti dynasty, ascended to power in 606 CE, ruling over northern India until 647 CE. Born in 590 CE in Sthanvishvara, part of the Pushyabhuti Kingdom (modern-day Thanesar, Haryana), he was the son of Prabhakaravardhana, a valiant leader who had successfully thwarted the Alchon Hun invaders.

Harsha’s lineage and early experiences shaped his destiny. His elder brother, Rajyavardhana, ruled over Thanesar, contributing to the family’s legacy. At the zenith of his reign, Harsha’s dominion extended across much of northern and northwestern India, with the Narmada River marking its southern boundary. Kannauj became his imperial capital, symbolizing the heart of his empire.

While Harsha’s ambitions reached far, his expansion encountered a setback in the Battle of Narmada, where Emperor Pulakeshin II of the Chalukya dynasty halted his southern penetration. Despite this defeat, Harsha’s realm flourished, fostering an era of peace and prosperity. His court in Kannauj became a beacon of cosmopolitanism, drawing scholars, artists, and religious figures from diverse backgrounds.

The renowned Chinese traveler Xuanzang lauded Harsha in his accounts, praising the king’s justice and generosity. Harsha’s life found immortalization in the Harshacharita, penned by the Sanskrit poet Banabhatta. The biography not only chronicled his association with Sthanesvara but also highlighted the defensive fortifications, including walls and a moat, as well as the grandeur of his palace, featuring a two-storied Dhavalagriha, or white mansion.

Harsha’s legacy transcends his military triumphs; it is the enduring imprint of a sovereign who, against the backdrop of conflict, cultivated an empire that radiated cultural richness and intellectual vibrancy.

Religio-cultural background of Harsha’s time:

Harsha emerges from the historical tapestry of ancient India as a figure of profound religious eclecticism. His inscriptions and seals reveal a fascinating mosaic of beliefs within his family, showcasing a remarkable synthesis of Hindu and Buddhist traditions. Harsha’s ancestors are described as worshippers of the Hindu sun god, Surya, while his elder brother embraced Buddhism. Harsha himself, however, identified as a Shaivite Hindu, a devotion underscored by the title Parama-maheshvara, signifying his supreme dedication to Lord Shiva.

The multifaceted nature of Harsha’s religious inclinations finds expression in his literary work, particularly in the play Nāgānanda. This dramatic masterpiece narrates the tale of the Bodhisattva Jīmūtavāhavana, and notably begins with an invocatory verse dedicated to the Buddha, depicting him triumphing over Māra. Shiva’s consort, Gauri, assumes a pivotal role in the play, using her divine power to resurrect the hero. The play intricately weaves together elements of Buddhism and Shaivism, offering a glimpse into Harsha’s intricate spiritual tapestry.

According to the accounts of the Chinese Buddhist traveler Xuanzang, Harsha’s religious pursuits extended beyond the pages of his literary creations. Xuanzang portrays Harsha as a devoted Buddhist who implemented significant reforms. Harsha banned animal slaughter for food, established monasteries at the sacred sites associated with Gautama Buddha, and erected numerous towering stupas along the Ganges river. Harsha’s philanthropy manifested in the construction of well-maintained hospices for travelers and the destitute along the highways of India. The annual assembly of global scholars, the charitable alms bestowed upon them, and the grand assembly called Moksha held every five years showcased Harsha’s commitment to religious pluralism and social welfare.

Despite Xuanzang’s vivid portrayal of Harsha as a Buddhist, historical nuances suggest a more nuanced reality. Harsha’s own records distinctly label him as a Shaivite Hindu. The possibility of his conversion to Buddhism, if at all, seems to have occurred in the later stages of his life. Scholars such as S. R. Goyal and S. V. Sohoni argue that Xuanzang’s narrative, while capturing Harsha’s patronage of Buddhists, may have misconstrued his personal faith. The historical landscape, therefore, paints a picture of Harsha as a ruler who, far from being confined to a singular religious identity, embraced a diverse tapestry of beliefs and practices.

In essence, Harsha’s religious eclecticism becomes a lens through which we glimpse the complexity of his reign. The convergence of Hinduism and Buddhism in his life and rule exemplifies a harmonious coexistence of diverse religious traditions. Harsha’s legacy transcends mere conquests and literary contributions; it reflects a ruler whose spiritual journey mirrored the rich tapestry of beliefs woven across the landscape of ancient India.

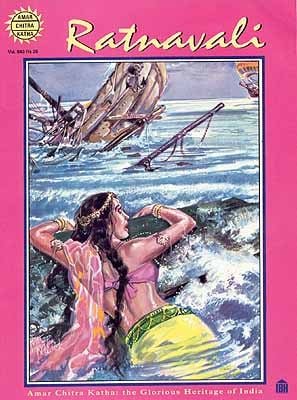

Ratnavali: Love and Intrigue within Political Confines

The visionary Indian emperor showcases his literary brilliance in the creation of the Sanskrit drama “Ratnavali.” Amidst the grand tapestry of courtly life in Kaushambi, Harsha weaves a captivating narrative around the valiant and romantic King Udayana, his first wife Vasavadatta, and the intriguing introduction of Ratnavali, a princess from the distant island kingdom of Simhala. What unfolds is a comedic tale set against the backdrop of love, misunderstandings, and political intricacies. Harsha’s intricate storytelling brings to life a rich array of characters, from the loyal and cunning minister Yaugandharayana to the clever friend Susangatha. The drama unfolds with layers of complexity, fueled by Harsha’s masterful portrayal of the characters’ emotions and motivations. The play not only explores themes of love and courtly relationships but also delves into political schemes and the consequences of deception.

Within this captivating tale, Harsha artfully introduces elements of suspense and romantic entanglements, keeping the audience engrossed in the fate of the characters. The setting of Kaushambi provides a vibrant backdrop for the unfolding drama, and Harsha’s nuanced portrayal of court life adds depth to the narrative. Through “Ratnavali,” Harsha transcends his role as a monarch and reveals himself as a skillful playwright, adept at capturing the complexities of human relationships and the intrigues of royal courts. The enduring appeal of “Ratnavali” lies not only in its dramatic flair but also in its exploration of the human experience, making it a timeless piece of literature attributed to the multifaceted legacy of Emperor Harsha.

The tale of the Snakes:

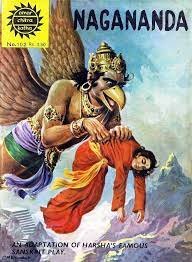

Nagananda, a Sanskrit play attributed to Emperor Harsha, stands as a pinnacle of classical Indian drama. Comprising five acts, it intricately weaves the tale of Jimutavahana, a prince of divine magicians (vidyādharas), and his sacrificial journey to save the Nagas. What sets “Nagananda” apart is its profound invocation to Buddha in the Nandi verse, recognized as one of the finest examples of dramatic compositions.

The play unfolds as Jimutavahana embarks on a selfless mission, sacrificing his own body to prevent the divine Garuda from claiming the life of a Naga prince. The narrative deftly intertwines elements of devotion, sacrifice, and divine intervention, creating a tapestry that resonates with timeless themes.

Central to the storyline is the invocation to Buddha at the beginning of the play, portraying the Bodhisattva Jīmūtavāhavana. The verses dedicated to the Buddha, depicting his triumph over Māra, contribute to the spiritual depth of the narrative. Shiva’s consort Gauri assumes a significant role, employing her divine power to resurrect the hero and infusing the play with elements of mysticism.

The first act unfolds in the penance-grove near the temple of Gauri, where Jimutavahana contemplates a life of service to his aging parents in the scenic Malaya Mountains. The play masterfully introduces the character’s internal conflict, balancing duty and personal desires, against the backdrop of the captivating natural setting.

While the story of Jimutavahana can be traced back to earlier works like the Kathasaritsagara and Brihatkathamanjari, Harsha’s rendition in “Nagananda” showcases his originality and creativity. Despite drawing inspiration from the Brihatkatha of Gunadhya, composed in the 1st century A.D., Harsha’s play, crafted in the 7th century A.D., deviates from the main narrative and incorporates his distinctive ideas.

Harsha’s “Nagananda” thus emerges as a captivating blend of classical storytelling, religious devotion, and inventive theatricality. The play’s enduring charm lies not only in its adherence to traditional themes but also in Harsha’s unique interpretation and presentation, making it a timeless contribution to the rich tapestry of Sanskrit drama.

Young adult rom-com, in Sanskrit

“Priyadarsika,” a romantic comedy in four acts, unfolds as a vibrant narrative named after its heroine, the enchanting daughter of Drdhavarman, the King of Anga. The play draws its plot from the semi-legendary life of King Udayana, also known as Vatsaraja, as chronicled in the Brhatkatha of Gunadhva. The tale of Udayana’s romantic escapades, entwined with the loves and adventures of the captivating Priyadarsika, echoes a theme that resonated widely in ancient India, evident from references by numerous Sanskrit poets.

At its core, “Priyadarsika” is a celebration of love and comedic intrigue, inviting the audience into the courtly realm of Drdhavarman and the romantic escapades of his daughter. The popularity of the narrative extends beyond its engaging plot, as it offers a glimpse into the cultural milieu of ancient India, exploring themes of love, royal relationships, and the vibrant tapestry of courtly life.

The significance of “Priyadarsika” is further accentuated by its comprehensive treatment. The play is accompanied by an exhaustive introduction, a concise yet illuminating Sanskrit commentary, various readings, and a literal English translation. Its meticulous presentation showcases the richness of Sanskrit literature, allowing readers to delve into the nuances of the plot, characters, and cultural references embedded in the text.

First translated into English in 1923 by G. K. Nariman, A. V. Williams Jackson, and Charles J. Ogden, “Priyadarsika” found a place in the Columbia University Indo-Iranian Series. This translation not only opened the doors for a wider audience to appreciate the play but also highlighted the scholarly efforts to preserve and share the treasures of ancient Indian literature. Through “Priyadarsika,” the audience is invited to explore the timeless charm of romantic comedies in the classical Sanskrit tradition, witnessing the enduring appeal of narratives that transcend the boundaries of time and culture.

Emperor Harsha’s rule stands as a remarkable chapter in Indian history, characterized by its grandeur and enduring legacy. Beyond military conquests, Harsha’s greatness lies in his ability to foster a realm of peace and prosperity, evident in the cosmopolitan court that attracted scholars, artists, and religious figures. Harsha’s literary prowess, showcased in plays like “Ratnavali,” “Nagananda,” and “Priyadarsika,” further solidifies his greatness. Through these literary masterpieces, Harsha not only demonstrated his multifaceted talents but also left a timeless imprint on classical Sanskrit drama. The narratives, rich in cultural nuances, continue to resonate through the ages, inviting modern readers to appreciate the depth of Harsha’s vision and the enduring charm of his literary contributions. Harsha’s rule, marked by a harmonious blend of governance and cultural patronage, transcends the boundaries of time, standing as a testament to the grandeur of an era that remains etched in the collective memory of India’s rich heritage.