Bandhani– The Ancient Handicraft Art of Western India.

- Lifestyle Ancient history Asian history

Khadija Khan

Khadija Khan- December 26, 2022

- 0

- 655

The Sanskrit verbal root bandh is where the word “bandhani” originates (“to bind, to tie”).

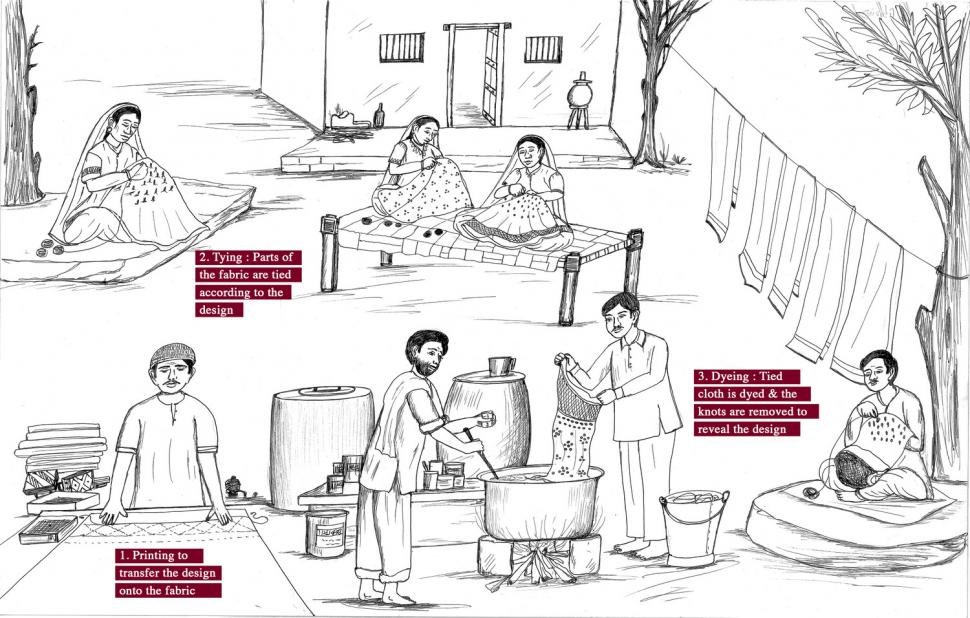

Bandhani often referred to as bandhej, is a type of tie-and-die in which the clothing is adorned by being bound into many ties. “Banda” is a word that signifies “knot.” With the bandhani process, patterns are produced by repeatedly dying a cloth that is tightly tied with thread. It is the oldest technique for creating sarees, odhnis, and turbans.

The majority of Bandhani production facilities nowadays are found in Gujarat, Rajasthan, Sindh, Punjab, and Tamil Nadu, where it is known as Sungudi. In Pakistan, it is referred to as chunri. The Indus Valley Civilization, where dyeing was practised as early as 4000 B.C., is where the earliest records of bandhani can be found. The paintings from the sixth century that chronicle the life of Buddha and were discovered on the wall of Cave 1 at Ajanta provide the oldest illustration of the most prevalent form of Bandhani dots. In 300 BC, texts from Alexander the Great that discuss the exquisite Indian printed cotton make reference to this form of art.

The first Bandhani saree was worn during Bana Bhatt’s Harshacharita in a royal wedding, according to evidence from historical texts. It was thought that a bride’s future may be brightened by donning a Bandhani saree.

For centuries, dyers have experimented with using various ingredients, both natural and man-made. There are other attempts using various binding and tying methods to design patterns on fabrics dipped in dye. In India, many other tie-dye techniques have been used.

This is why India is the country where this wonderful handicraft originated as a consequence.

Dyes also have a rich and colourful history in India. In addition to being used in contemporary Indo-western and traditional clothing, this tie-dye art form has been around for a long time.

Bandhani textile is adorned by picking the fabric with the fingernails into numerous small binds to create a symbolic pattern. This method requires accuracy, talent, and enthusiasm. The method involves dying a piece of fabric that has been tightly knotted with threads at various locations, producing a variety of designs depending on how the fabric is tied.

The most remarkable feature is that these knots are produced precisely and with exquisite design; they are not created at random. Chandrakal, Shikari, Pawan Baug, Khombi, Gharchola, Leheriya, Ekdali, Mothra and other common styles are produced.

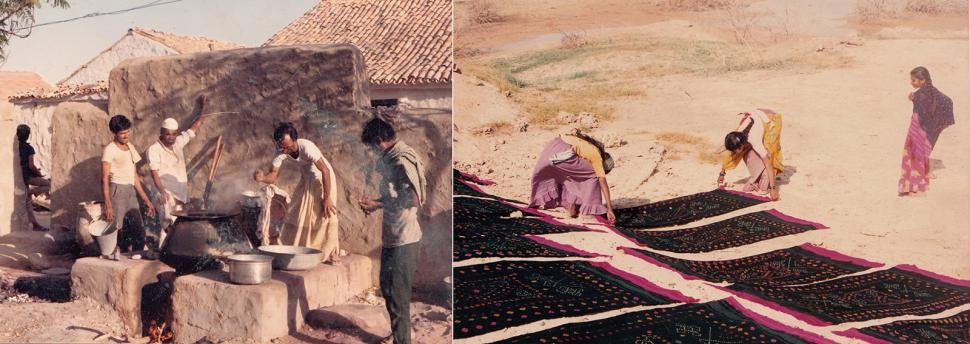

They were formerly tied in a particular design knot and are then painted in a range of hues. After drying, they are opened while retaining the fabric’s original colour, creating an exquisite pattern of hues and patterns. The drying procedure can take up to 4-5 hours on a bright day, 6-7 hours in the winter, and two days in the monsoon.

In bandhani– yellow, red, blue, green, and black are the primary colours used. After processing, bandhani art produces a range of symbols, such as dots, squares, waves, and strips. Bandhani items can be coloured both naturally and artificially.

Natural colours are the primary ones. Actually, bandhani uses only dark hues; no light hues are employed, and the fabric used for the backdrop is often black and red. And in many cultures, these vivid colours have diverse meanings.

Red is the sign of an early marriage. And is said to bestow good fortune and a prosperous future to a newlywed lady.

Yellow heralds the arrival of spring and endless delight.

The colour of a yogi is saffron.

For mourning, its black.

- Some types of knots

Ekdali: One knot

Trikunti: Three knots

Chaubandi: Four-knot

Dungar Shahi: Mountain-pattern

Boond: A little knot and a deep, tear-like knot.

- Materials used to tie

Nakhli: On the ring finger, an artificial nail composed of plastic or metal is referred to as a “nakh.” The tip on the nakhli allows for complex bandhani tying.

Bhungli: It is a thin, narrow pipe used to better hold the cloth when making the knot. Typically, it is constructed of plastic and glass. The knot is tied by making the thread used for tying pass through the bhungli.

Needles: To create the stitch resist pattern known as “kodi’s,” needles are utilised.

Perforated polythene sheets: These days, perforated polythene sheets have taken the role of wooden blocks. Perforations are constructed in patterns to allow printing through polythene sheets.

Threads (Dori): are typically employed to denote boundaries, straight lines, and pallus. It is placed on the fabric after being dipped in geru, Robin blue, and an impression is created.

Geru: The red paste used for printing in a red oxide clay solution is referred to as geru.

Black Robin: It serves as a printing industry replacement for geru.

- Materials used to dye and finish

Wooden sticks are used to stir the dye solution. Rubber gloves, metal spoons, buckets, and tagaras, as well as a gas burner are also used. To rinse the extra water and to wash the dyed fabrics, dyeing machines and washing machines are utilised.

In addition to being a masterful work of art, the allure of Bandhani has led to its commercialization. This resulted in a large variety of raw materials and items being utilised for this type of painting. Originally only used for saris and odhanis, this ancient technique is now performed on fabrics like georgette, nylon, and other mixes rather than cotton, gazi, and silk, much like bandhani. Now available on the art market are pillowcases, duppatas, folders, bags, handbags, and clothing like shirts.

Bandhani is connected to the Gujarati regions of Jamnagar and Kutch. The cloth is hand-tied specifically. Generation after generation has passed down the craft of creating these vibrantly coloured and designed cotton and silk garments. It is known that the Kutchi Khatris– Muslims, and Sindhis all practised this technique.

Even though it originated in India, it is now practised in many nations, including Africa and Japan. As a result, this kind of art is used to create several Indo-Western clothing items, like odhanis and scarves. The number of tourists keeps increasing over the holiday season. Additionally, upkeep is quite inexpensive. However, keep in mind that you absolutely cannot iron them. The bandhani loses some of its strength. Therefore, it is recommended to dry clean or use low-heat methods.

Daily wear is possible with a straightforward bandhani-patterned salwar kameez. Leheriya sarees, lehengas, may all be worn throughout the day and ghatcholas at night. This clothing is suitable for both independent urban and domestic women, and both may wear it.

“The term “bandhani” refers to a variety of goods, not just saris. It can be made of cotton or silk and take the form of a turban, sari, or even dupattas. In Jamnagar and Kutch districts, the term “bandhani” refers to specific locations where this old craft was practised.” Atira’s research officer, RM Shanker, of The Ahmedabad’s textile industry research association said.

However, due to the brand being associated with inferior goods nowadays, this cloth stands the risk of losing its distinctiveness. The government intends to stop it by marking the genuine article with a geographical indication (GI) tag.

Bandhani, about which numerous books and records have been published, is genuinely surviving thanks to the artisans who have continued the trade of their forefathers despite great adversity. Some major artists include Abdul Jabbar Khatri, Daud Khatri, Ali Mohammad Isha and Mohammad Arif Khatri.

With the shifting market demands for bandhani, the artisans have also created variations based on the needs of the business. People need to be made aware of how many challenges the craftspeople have been dealing with. The declining market for handicrafts and the insufficient pay of the artisans are to blame since they can scarcely meet their most basic demands for existence.

- Factors responsible for a decline in craftsmen

Social and economic factors:

The intermediaries, like the traders, lead a comfortable existence by selling the craft to customers and making enough money to live a life of luxury. In contrast, the genuine craftsman who spent all of his time and effort making the artisan items goes days without even the most basic necessities. The craftspeople endure great hardship by going days without access to water. The local craftsmen and their families spend most of the day without power in a region like Surendarnagar where the temperature is constantly high.

Many skilled craftspeople have changed their careers or taken up labour jobs under traders since the market is shrinking and the wages are paid on a work basis.

Political factors:

The government facilities and assistance are the craftsmen’s biggest gripes. Craftsmen share their dilemmas about the uncaring government and other NGOs that arrive and promise them employment and more pay but in the end, take advantage of the craft and leave them as they were.

It is believed that if action is not taken to ameliorate their circumstances and rescue this dying craft, it will undoubtedly lose its esteem and practice.